As we continue our series on the early history of Illinois, here’s a chance to read one of our old Local History Room columns, first published in January 2012 before the launch of this blog . . .

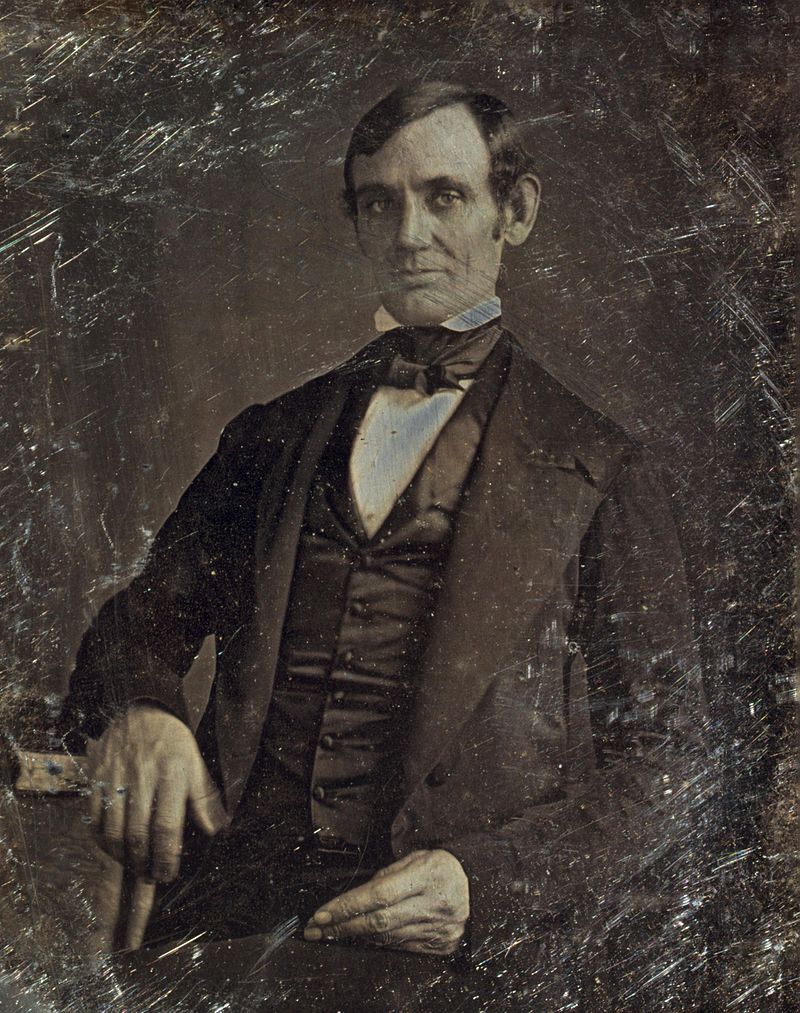

Among the earliest written records of Illinois and Tazewell County history are found in the journals of the French explorer Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (1643-1687), who is best known in Tazewell County for building a fort at the future location of Creve Coeur in January of 1680. The Pekin Public Library’s Local History Room has resources that can help to bring that story to life.

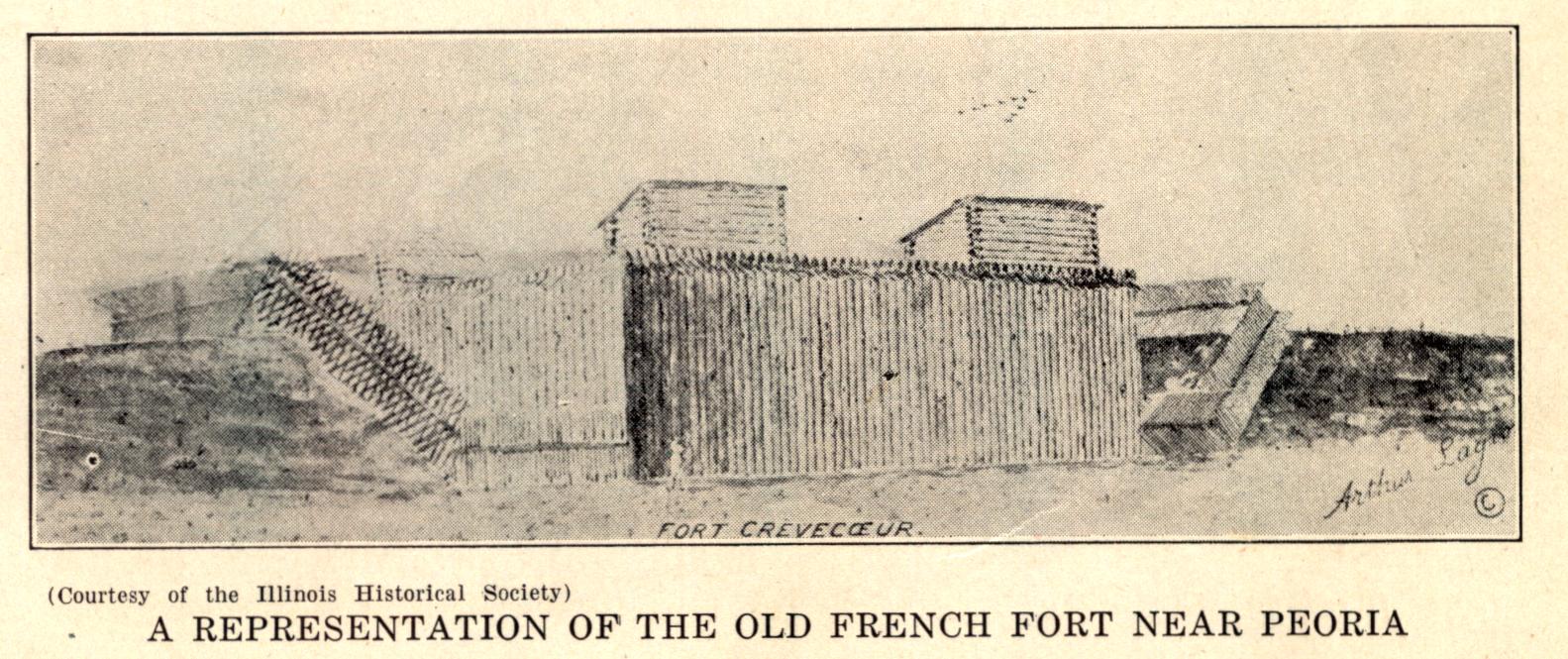

No one can say for sure exactly where La Salle’s “Fort Crevecoeur” was, though La Salle described the general area in his journals. He wrote, “On January 15, toward evening a great thaw, which opportunely occurred, rendered the river free from ice from Pimiteoui as far as [the place chosen for the fort]. It was a little hillock about 540 feet from the bank of the river; up to the foot of the hillock the river expanded every time that there fell a heavy rain. Two wide and deep ravines shut in two other sides and one-half of the fourth, which I caused to be closed completely by a ditch joining the two ravines.”

“Pimiteoui” was the Native American name for the area where the Illinois River widens to become what we now know as Peoria Lake. It was also the name of a Native American village located at the future site of Peoria. In his 1879 “History of Tazewell County,” p.33, Charles C. Chapman locates the fort “at the lower end of the lake, on its eastern bank . . . The place where this ancient fort stood may still be seen just below the outlet of Peoria lake.”

As we saw last time, the purpose of Fort Crevecoeur and the other forts the French built in the Illinois Country was to help France control the fur trade. The most likely place where this fort stood is in the low areas of Creve Coeur or possibly East Peoria, between Peoria Lake and the bluffs. Others have argued the fort was much further up the river, or far down river in the area near Beardstown, but neither of those locations fits La Salle’s description very well.

In a 1902 essay, “Historic Pekin!,” Pekin’s early historian W. H. Bates tells how La Salle and his party “landed at what is now Wesley City, Pekin Township, five and a half miles due north from Pekin, and built a large stockade fort on the high bluff above which he named Creve Coeur. “ Wesley City later was renamed Creve Coeur in memory of La Salle’s fort, and until recently the community has looked back to those days every spring and fall with events at Fort Crevecouer Park.

The fort did not last long. La Salle had to return to Canada in February, leaving Henri de Tonti (1649-1704) and a small garrison at the fort. In April, Tonti departed to consider the possibility of building a fort on Starved Rock, but during his absence, most of the garrison mutinied and destroyed the fort. The story of La Salle’s explorations and the brief existence of Fort Crevecoeur is related in some detail in John L. Conger’s 1932 “History of the Illinois River Valley.”

As for La Salle himself, he later founded a French colony on Garcitas Creek, Texas, on the Gulf of Mexico, but La Salle’s men mutinied and he was murdered by one of the mutineers on March 19, 1687, near modern Navasota, Texas.

Rare, early maps of the area show both Lake Pimiteoui and Fort Crevecoeur, but not in enough detail to ascertain the precise location of the fort. One of the earliest of those maps was drawn up in 1688 by Jean-Baptiste Louis Franquelin, who had served as La Salle’s draftsman in France in 1684. Franquelin’s 1688 map was ultimately based on a lost map drawn up by La Salle himself. Fort Crevecoeur and Pimiteoui Lake are also noted on Marco Vincenzo Coronelli’s 1688 map of North America. Coronelli got his information about Fort Crevecoeur from La Salle’s own 1682 Relation Officielle of his discovery of the mouth of the Mississippi River.

Reproductions of these and other early maps of Illinois and North America are included in “Indian Villages of the Illinois Country,” a remarkable atlas kept on file in the library’s local history room.