As National American Indian Heritage Month nears its end, this week we’ll take a look at Illinois’ Native American past and what one can learn about it at the Pekin Public Library’s Local History Room.

Recorded history in central Illinois reaches back not even four centuries, to the era of the European exploration and colonization of North America. But archaeology and anthropology enable us to learn about the thousands of years of human habitation in central Illinois prior to written records.

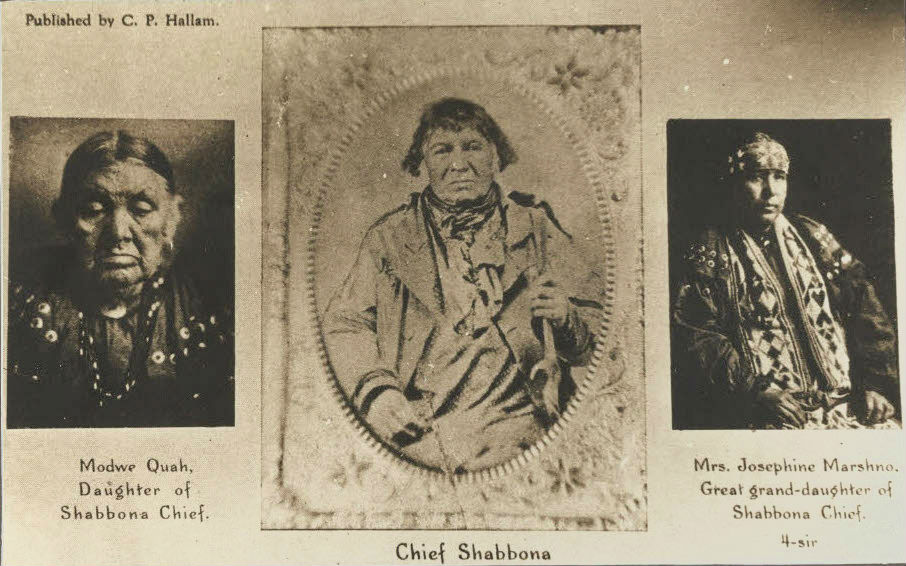

Naturally much of our local history involves the stories of the white settlers, and the bulk of the materials and resources in the Local History Room has to do with their story. But our local history collection does not neglect the peoples who arrived here first during forgotten past ages, and so from time to time this column has looked back at the original inhabitants of Tazewell County, especially during the period of the arrival of white settlers and the dispossession of the Native American tribes – recounting, for example, the life of Pottawatomi leader Shabbona who dwelt for a while in Pekin, or the Oct. 1812 raid of Illinois Territorial Gov. Ninian Edwards on Chief Black Partridge’s village which was located on the northeast shore of Peoria Lake in Fon du Lac Township.

Those who would like to learn more of the first-comers to Illinois can find a great deal of information in the publications on Illinois state history that may be found on the shelves of the Local History Room. Our collection also includes fascinating resources such as the atlas of “Indian Villages of the Illinois County,” which contains reproductions and descriptions of rare historical maps of North America and the Midwest dating from as early as the time of the French explorers of the Illinois River valley in the 1680s.

This atlas was one of the resources referenced by this column in 2012 when we told the story of the founding of Fort Crevecoeur. Another useful compilation in the Local History Room is John Leonard Conger’s 1923 “History of the Illinois River Valley.”

Those whose interest in the first nations of Illinois is more genealogical might want to search Helen Cox Tregillis’ 1983 volume, “The Indians of Illinois: A History and Genealogy,” which includes a lengthy and apparently exhaustive alphabetized list of Native American individuals who appear in the documents of Illinois history from 1642 to 1861, along with the title or description of the historical document where he or she was mentioned. Tregellis compiled this index from 43 different publications. Because Native Americans in earlier periods usually were illiterate and thus did not produce the written texts that are the basis of historical works and genealogical research, we are largely dependent on the texts and treaties of the white colonists for Native American history. Consequently, Tregellis’ index can be a great navigation aid for researchers.

One of the more recent additions to the Local History Room collection is Blake A. Watson’s 2012 “Buying America from the Indians: Johnson v. McIntosh and the History of Native Land Rights.” Watson’s book views Native American history through the lens of laws, treaties and the courts, exploring the impact of the 1823 U.S. Supreme Court ruling Johnson v. McIntosh, which, as Watson explains, set important legal precedents that determined the principles that still govern American Indian property rights today.

Although it’s a story that encompasses a broad sweep of U.S. history, Watson’s book also touches directly on Illinois and the land that would later become Tazewell County, and in the process Watson tells how land speculators and government agents obtained title to the Illinois country and displaced the native tribes.

Watson relates the story in a dispassionate and factual manner, but the story he tells is the same one that was emotionally evoked in James Stelle’s 1853 poem, “An Indian at His Father’s Grave,” which commences with these lines:

“Stop! Whiteman stop! This mound you see

Is where my father’s ashes lay;

‘Tis dearer far than life to me –

Oh! Do not force his child away.”

Stelle’s poem was published as the frontispiece to Tregellis’ book.