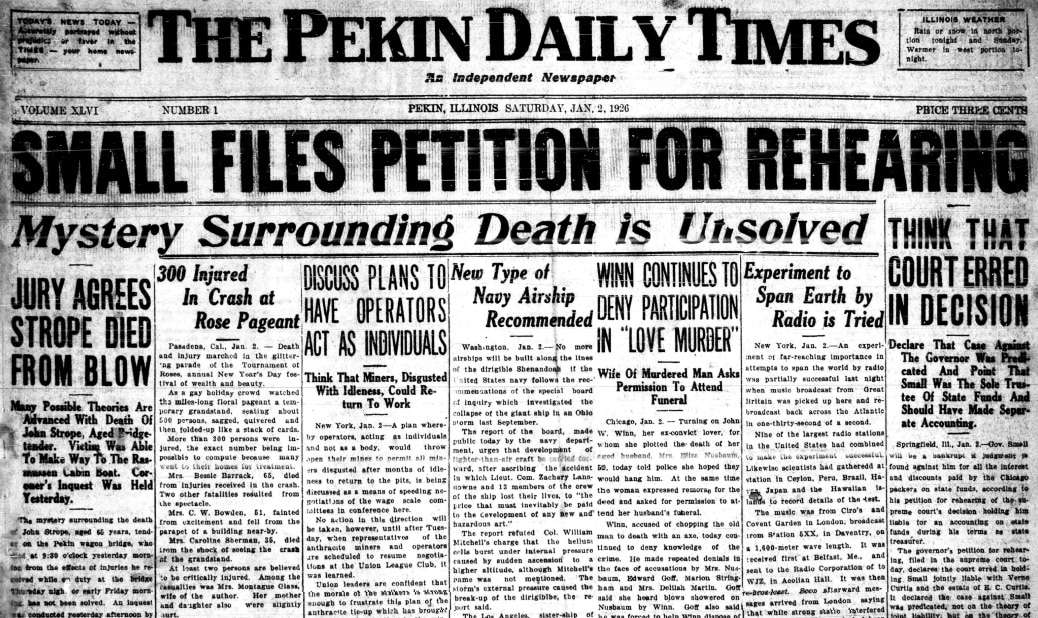

With this post to our Local History Room weblog, we conclude our series on a pair of sensational deaths that occurred in Pekin, Illinois, during the Prohibition Era. The Local History Room columns in this series, entitled “The Third Degree,” originally ran in the Saturday Pekin Daily Times from Sept. 15, 2012, to March 2, 2013.

THE THIRD DEGREE

By Jared Olar

Library assistant

Chapter Twenty-five

Aftermath and Epilogue

Voters finally achieve deputies’ ouster

The failure to convict Deputies Ernest L. Fleming and Charles O. Skinner of Martin Virant’s death provoked abortive attempts during the spring and fall of 1933 to oust Tazewell County Sheriff James J. Crosby and remove his entire force of deputies.

It was no surprise, then, that Crosby decided not to run for re-election in 1934. Crosby had two very good reasons not to run again: in addition to the simmering discontent over the Virant affair, Crosby’s health remained fragile following the nearly fatal heart attack he had suffered in November of 1932. In place of Crosby, the Tazewell County Democrats put up Lawrence Lancaster, while the Republicans opted for Pekin Chief of Police Ralph C. Goar.

In 1934, voter antipathy toward the Republican Party over the Great Depression was still very strong, and the midterm elections that year would again prove to be a near total rout nationally as well as at the state and local levels. In light of those facts, it is a testament to the intensity of popular dissatisfaction with the Tazewell County Sheriff’s Department that Goar’s photograph would end up on the front page of the Nov. 7, 1934 Pekin Daily Times under the headline, “ONLY G.O.P WINNER.”

The election of Goar ensured that the county would get a sheriff who would “clean house” and replace the deputies who were seen by many as Crosby’s cronies. Evidently voters did not trust that would happen if they replaced the Democrat Crosby with another Democrat. Goar also had an added advantage with the voters: He was the law enforcement officer who had personally arrested Deputy Skinner and had provided the grand jury with important testimony against him.

Sheriff Goar did not waste any time in getting around to the housecleaning at the Sheriff’s Department – on Dec. 1, 1934, his first day in office, it was out with the old and in with the new.

“Deputy Sheriff Fleming, who is retiring,” reported that day’s Pekin Daily Times, “will move to his residence property at 614 S. Eleventh street and Sheriff-Elect Ralph Goar will move into the jail residence . . . . Goar will assume the duties of sheriff. Elmer Eiler will be the office deputy under Sheriff Goar and Earl H. Whitmore of Pekin and Arthur Puterbaugh of Mackinaw are to be the outside deputies, Mr. Whitmore being the chief deputy. Sheriff Crosby, Deputies Fleming and Skinner will remain in Pekin, but have made no announcement of their future plans . . . .”

Elliff departs, but no comeback for Dunkelberg

The failed prosecutions of Fleming and Skinner, and the unraveling of the case against Petje, also did little to endear voters to Tazewell County State’s Attorney Nathan T. Elliff, who perhaps wisely did not seek a second term in 1936. Instead, it was a race between Democratic candidate R. L. Russell, a former mayor of Pekin, and former State’s Attorney Louis P. Dunkelberg, who had been defeated by Elliff in 1932.

However, Dunkelberg again was defeated at the polls. He would not seek his old office again, but would remain in Pekin, where he was a part of the law firm of Dunkelberg and Rust, located on the second floor of the old Pekin Times building. Dunkelberg died on March 27, 1976, at age 79. He is buried in Lakeside Cemetery in Pekin.

As for Elliff, he also never again sought his former job of state’s attorney. In 1940, he joined the U.S. Department of Justice, returning to his law practice in Pekin in 1947 and becoming an active community leader. He died on Dec. 3, 1993, at age 88, and also is buried in Lakeside Cemetery.

Poor health, heart troubles claim Black, Reardon, Allen, and Crosby

Most of the other main players in this drama died much earlier than Dunkelberg and Elliff. After successfully defending Deputies Fleming and Skinner in the Virant manslaughter trial, Jesse Black Jr.’s health failed. Following several months of illness, Black died on Oct. 11, 1935, at age 64. His fellow attorney in the Virant case, William J. Reardon, died of heart trouble on June 27, 1941, the day before his 63rd birthday. Black and Reardon are both buried in Lakeside Cemetery.

After losing his re-election bid in 1932, Tazewell County Coroner Dr. Arthur E. Allen, who investigated the Lewis Nelan and Martin Virant deaths, continued his medical practice in the Green Valley area until 1946, when he moved to California. He served as house physician for the Santa Fe Railroad at Los Angeles until suffering a heart attack in March 1961 from which he never fully recovered. He died at age 82 on May 30, 1963, in West Los Angeles, and is buried in Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego.

Not quite five years after the end of his single term as Tazewell County Sheriff, James J. Crosby at age 72 succumbed on May 23, 1939, to the heart problems that had plagued him for several years. The Pekin Daily Times published a front page obituary and tribute to Crosby, recalling his many years as a local teacher and school administrator, and respectfully passing over the controversies of his time as sheriff. He is buried in Lakeside Cemetery.

Fleming, Skinner, and Garber summoned to Highest Court

The Daily Times showed similar respect for Fleming, who died at age 81 on March 22, 1955. His obituary notes only that he was “a former Tazewell county sheriff for several terms and a baker here for many years.” He was entombed in Lakeside Mausoleum.

After Sheriff Goar dismissed him from the Sheriff’s Department, Skinner later moved back to East Peoria, where he died at age 54 on June 7, 1938. He is buried in Springdale Cemetery in Peoria. Deputy J. Hardy Garber also left the area after Goar dismissed him. He served in both the Army and Navy during World War II, settling in Des Moines, Iowa, after the war. He died on March 26, 1968, at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Iowa City, and was buried in Glendale Veterans Cemetery in Des Moines.

What of the Nelan defendants?

Of the three defendants in the Nelan case, Edward Hufeld later served in the Army during World War II, returning to East Peoria after the war. He never married, and he died at age 62 at Proctor Hospital in Peoria on March 20, 1965, being buried in Fondulac Cemetery, East Peoria. Frank Keayes Jr. moved to Pekin, dying at age 82, also at Proctor Hospital, on Dec. 26, 1982, also being buried in Fondulac Cemetery.

As for John Petje, following his acquittal on charges of murder, he remained in East Peoria and lived until age 62. On March 26, 1943, the Pekin Daily Times reported on page 2 that “Mr. Tetje (sic) was found yesterday afternoon at 2:30 o’clock hanged by a light cord fastened to a door sill in his house on S. Main Street.” The following day, the Daily Times reported that a coroner’s inquest jury ruled Petje’s death a suicide “while despondent over ill health.”

The reports of Petje’s death do not mention the Nelan case, saying only that Petje was “a prominent East Peoria citizen” without explaining what had made him “prominent.” He is buried in Parkview Cemetery in Peoria, the same cemetery where the family of Martin Virant laid him rest.

APPENDIX AND AUTHOR’S AFTERWORD

The decision to re-tell the scandalous history of the Lew Nelan and Martin Virant killings came about in the late summer or early autumn of 2012, when David Perkins of the Tazewell County Genealogical & Historical Society shared with the Pekin Public Library copies of some old Pekin and Peoria newspaper articles and funeral home records pertaining to the Nelan and Virant cases. At first it appeared that the stories could be succinctly reviewed in two or three weekly “From the Local History Room” columns in the Saturday Pekin Daily Times. As I researched these stories, however, it became clear that they needed a much fuller treatment which would call for an extended re-telling in a weekly serial format in the newspaper.

Prior to the publication of the “Third Degree” serial in the Pekin Daily Times in 2012-2013, the deaths of Nelan and Virant had been all but forgotten in Pekin. The late Robert Dubois, during his tenure as Tazewell County Coroner, once told me of the Nelan and Virant cases in a conversation with me around 2003. Dubois, who had read the inquest file on Virant’s death, explained at some length how the evidence and observations at the death scene made obvious that Virant was already dead before he was hanged. Though I found the facts Dubois recounted to be remarkable, I did not commit these details to memory (not even the victims’ names) and soon forgot our conversation, and only remembered that he had talked about it while I was in the process of researching their deaths for the Pekin Public Library’s weekly “From the Local History Room” column.

I doubt very many others in our day besides men such as Coroner Dubois or those with an interest in local history knew of Nelan and Virant and the controversies surrounding their deaths, which were probably all but forgotten in Pekin and Tazewell County prior to 2012. Although the saga frequently was front-page news in 1932-1933, the long and sorrowful story was reduced to a single paragraph on page 69 of the 1949 Pekin Centenary, which included a historical narrative that was mainly researched and written by retired Peoria Journal Star editor Charles Dancey:

“The discovery of the body of Martin Virant, a material witness, in the Tazewell county jail caused a storm which lasted for months. After the inquest there was a near lynching of accused deputies, who were later tried on manslaughter charges that Virant died under the ‘third degree’. Even after their acquittal, there was an effort to impeach the entire sheriff’s office on the part of the Tazewell county board of supervisors.”

That somewhat inaccurate paragraph would later appear in almost identical form in the historical narrative of the 1974 Pekin Sesquicentennial volume, on page 173:

“After a material witness named Martin Virant was found dead in his cell at the Tazewell County Jail, there was a storm of public outrage which nearly resulted in the lynching of some accused deputy sheriffs. (They were subsequently tried for manslaughter on charges that Virant died under the ‘third degree.’) There was an effort to impeach the entire Sheriff’s office by the County Board.”

As we have seen, the few lines in the Centenary and Sesquicentennial volumes omit several important details and really only begin to hint at that “storm which lasted for months.”