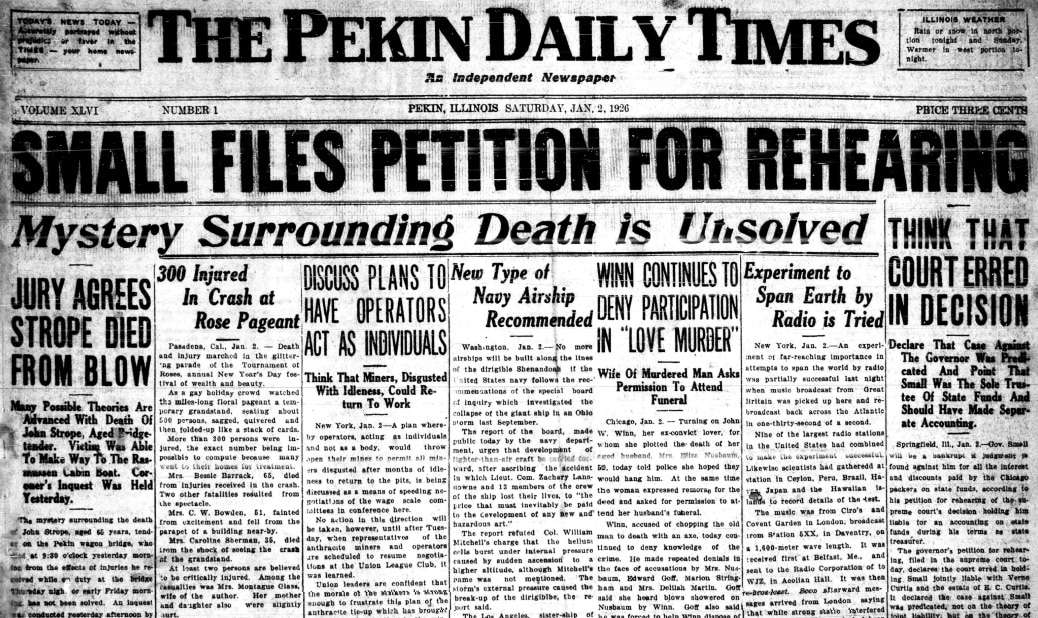

With this post to our Local History Room weblog, we continue our series on a pair of sensational deaths that occurred in Pekin, Illinois, during the Prohibition Era. The Local History Room columns in this series, entitled “The Third Degree,” originally ran in the Saturday Pekin Daily Times from Sept. 15, 2012, to March 2, 2013.

THE THIRD DEGREE

By Jared Olar

Library assistant

Chapter Twenty-four

A sudden ending to John Petje’s murder trial

After months of delays followed by an unusually slow jury selection process, the murder trial of East Peoria speakeasy operator John Petje finally got under way on Thursday, Dec. 7, 1933.

On Friday morning, Dec. 8, it all came screeching to a very sudden halt.

Tazewell County State’s Attorney Nathan T. Elliff called two witnesses to the stand that morning: William Peters, brakeman for the C. and I. M. railroad, and Engineer W. S. Kirkwood. Peters and Kirkwood operated the train that ran over Lew Nelan in the early morning hours of Sunday, Aug. 28, 1932.

Nelan, along with two of Petje’s acquaintances, Frank Keayes Jr. and Edward Hufeld, had been drinking at Petje’s speakeasy on Saturday night. At the coroner’s inquest into Nelan’s death, Keayes and Hufeld testified that Petje and Nelan had fought, and that Petje struck Nelan on the head with an iron bar. According to their inquest testimony, thinking Nelan was dead, the three men took Nelan’s body to the railroad tracks nearby so he would be run over.

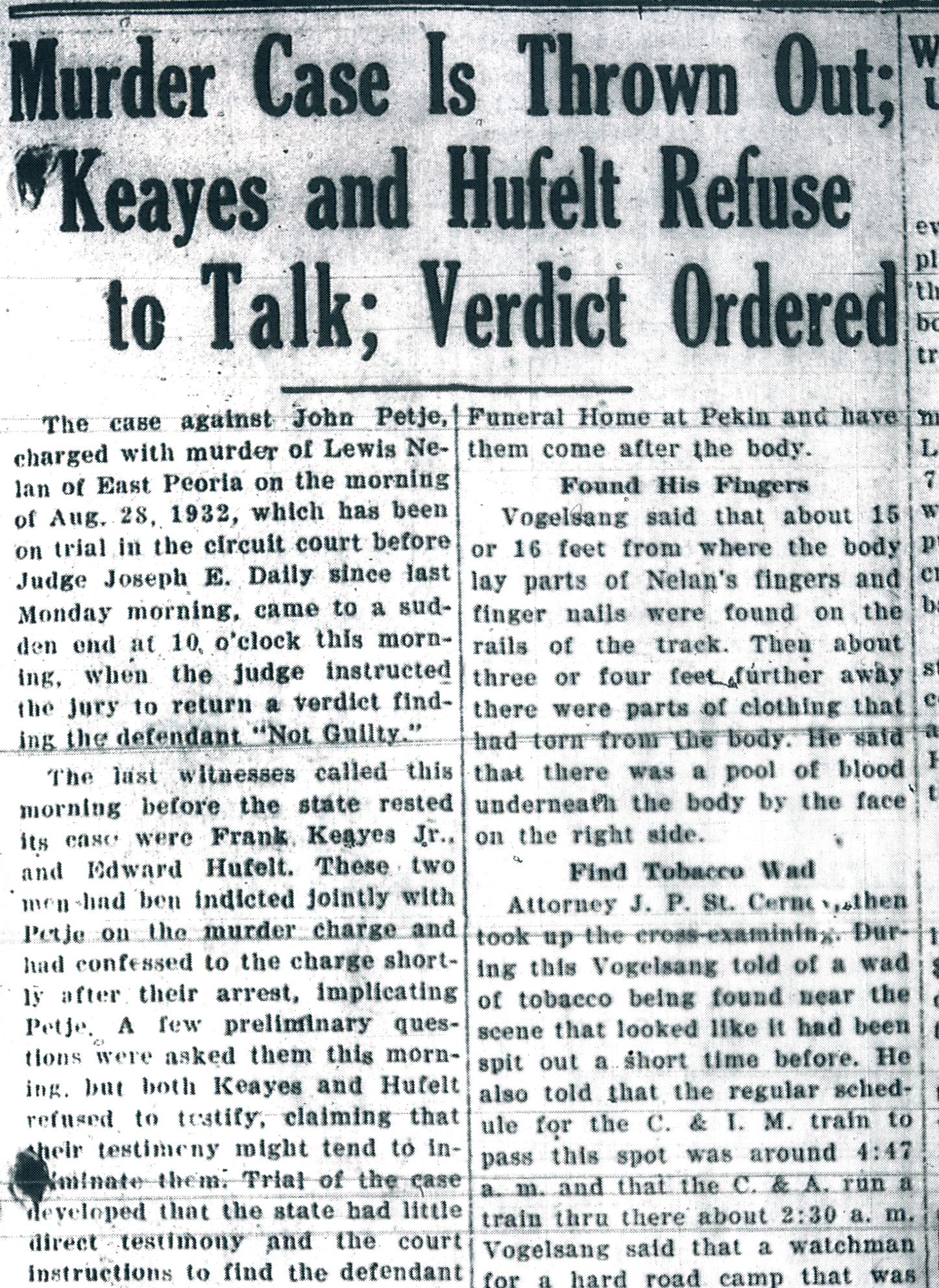

The testimony of Keayes and Hufeld would be crucial in establishing that Petje was guilty of Nelan’s murder. However, according to the Pekin Daily Times, after Petje’s attorney, James P. St. Cerny, had concluded his cross-examination of Engineer Kirkwood around 10 a.m., “Attorneys St. Cerney (sic) and P. A. D’Arcy and State’s Attorney Elliff gathered in front of the judge and they had written into the court’s records certain facts as to why the state did not call in Frank Keayes Jr. and Edward Hufelt (sic) as witnesses.”

Judge Joseph E. Daily then questioned Keayes as to where he was on the evening of Aug. 27, 1932.

Keayes replied, “I refuse to testify.”

Judge Daily asked him why he refused, and Keayes replied, “I might incriminate myself,” availing himself of his constitutional right against self-incrimination guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment.

Next, the judge called Hufeld and asked him the same two questions, and Hufeld responded in the same words that Keayes had used.

Judge Daily dismissed Hufeld, and then, turning to the jury, instructed the jurors to return a directed verdict of “not guilty.”

With Keayes and Hufeld “taking the Fifth,” the state could not tie Petje to Nelan’s death. “Trial of the case developed that the state had little direct testimony and the court instructions to find the defendant not guilty came as little surprise to those who had been following the trial,” the Pekin Daily Times explained.

Elliff’s attempted prosecution of Petje had followed a similar course as, and had collapsed in much the same way that, his prosecution of Sheriff’s Deputies Ernest Fleming and Charles Skinner had.

In the case of Martin Virant’s death, Elliff dropped the charges against Deputy Frank Lee and then went on to lose the case when he and his fellow prosecutors were unable to tie Fleming and Skinner to Virant’s beating and hanging.

In the case of Nelan’s death, Elliff dropped the charges against Keayes and Hufeld and then lost the case when he had no way to link Petje to Nelan’s beating and the dumping of his body on the track.

Tazewell County’s residents had now seen the unraveling of the prosecutions in the cases of two related, very sensational homicides, along with fruitless attempts to oust the county sheriff and his deputies.

These events helped to create a general sense of great dissatisfaction with the Tazewell County Sheriff’s Department and the State’s Attorney’s Office, and a debilitating loss of confidence in both elected offices.

This inevitably would have notable political repercussions.

Next week: Aftermath and epilogue.