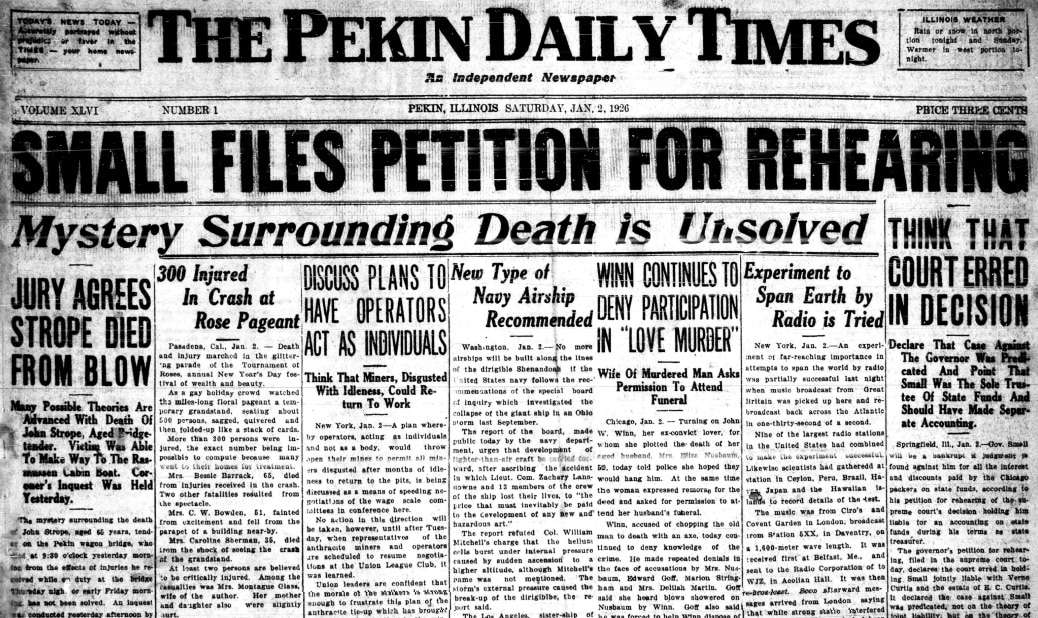

With this post to our Local History Room weblog, we continue our series on a pair of sensational deaths that occurred in Pekin, Illinois, during the Prohibition Era. The Local History Room columns in this series, entitled “The Third Degree,” originally ran in the Saturday Pekin Daily Times from Sept. 15, 2012, to March 2, 2013.

THE THIRD DEGREE

By Jared Olar

Library assistant

Chapter Twenty-two

County board to Sheriff Crosby: ‘Clean house’

Terribly disappointed by the acquittal of Tazewell County Sheriff’s Deputies Ernest Fleming and Charles Skinner, a large group of citizens presented a heavy stack of signatures to the Tazewell County Board on Monday, March 20, 1933, calling for the impeachment of Sheriff James J. Crosby and the removal of his entire force.

The Pekin Daily Times reported that about 2,310 people had signed the petition, and reported the following approximate breakdown of signatures by township:

Mackinaw, 160

South Pekin, 200

Washington, 175

Fondulac, 300

Deer Creek, 20

Tremont, 40

Delavan, 100

Groveland, 80

Morton, 25

Green Valley, 70

Hittle, 140

Dillon, 250

Little Mackinaw, 80

Hopedale, 60

Spring Lake, 170

Pekin, 190

Miscellaneous, 110.

The county board referred the matter to Tazewell County State’s Attorney Nathan T. Elliff for his legal opinion. Elliff quickly prepared a report which he presented to the board that very afternoon.

“It is my opinion that there is no power of impeachment in the board of supervisors. It is my further opinion that the board of supervisors has no power to remove from office members of the sheriff’s force. The only action which the board can take upon the petition is, in my opinion, to make such recommendations as the members may deem fit and proper under the circumstances.”

Elliff also offered to contact the Illinois Attorney General for his opinion. The county board requested that he do so, and the Attorney General confirmed his opinion.

Having considered Elliff’s advice and the opinion of the Attorney General, the board reconvened in special session the following day and issued a unanimous and urgent statement.

“Whereas,” the county board declared, “it is the opinion of the said board of supervisors that the said Ernest L. Fleming, C. O. Skinner and Frank Lee are, because of the public opinion existing in said Tazewell county, not qualified to continue in their capacities as deputy sheriffs of said Tazewell county, inasmuch as they lack the confidence and support of the people in general in said county.

“Therefore, we the members of the Board of Supervisors of Tazewell County, Illinois, do hereby recommend to the honorable James J. Crosby, sheriff of Tazewell County, Illinois, that the said deputy sheriffs . . . be dismissed from their offices as deputy sheriffs of said Tazewell County.”

Sheriff Crosby did not immediately respond to the county board’s public recommendation, but rumors began to fly that some or all of the deputies implicated in Virant’s death had tendered their resignations.

However, on Thursday, March 23, the Pekin Daily Times published a short front page notice with the headline, “No Statement to Make at This Time, Says Sheriff.”

“Sheriff Crosby said this morning that he had no statement to make at this time, relative to the recommendation of the board of supervisors that he dismiss Deputies Fleming, Skinner and Lee, and would probably have none until he had conferred with his attorney, Jesse Black. There has been no change in his office force and no resignations as had erroneously been rumored.”

In fact, Sheriff Crosby would have nothing further to say publicly about the county board’s recommendation. He decided simply to ignore the board’s statement, choosing to weather the storm of controversy until it had blown over. He could not be impeached and was not subject to voter recall, and he was endowed by law with wide discretion in the use of his deputizing power, so the petition drive to remove him and his deputies was to no avail.

And there the matter would rest for the remainder of the spring and the whole of the summer of 1933. For a while it appeared that the storm had blown over.

In September, however, the controversy made its way back onto the pages of the Pekin Daily Times (although not the front page this time). At that time, a small group of citizens filed a complaint of criminal malfeasance against the sheriff.

In the edition of Sept. 13, 1933, the Daily Times announced, “Sheriff Case Is Revived; To Refer It to Grand Jury,” saying, “Among the several matters which will be presented or referred to the grand jury is a complaint against Sheriff James J. Crosby, charging that official with omission of duty and malfeasance of office. The complaint, signed by four persons, was filed by Neal D. Reardon in the office of the circuit clerk and by that official turned over to State’s Attorney Elliff.”

The Daily Times noted that there was doubt whether the complaint had been filed under the proper section of the law. That morning, Elliff affirmed that the case would be “referred” to the grand jury for their consideration, but it might not be “presented” to the grand jury, meaning there wouldn’t necessarily be a presentation of evidence and summoning of witnesses.

Just like the petition drive, however, this attempt to remove the sheriff also failed. On Sept. 20, the Daily Times reported that the grand jury had decided not to take up the criminal complaint against Crosby.

So ended the attempts to oust the sheriff and remove his tarnished deputies. Thwarted in the courts and at the level of county government, the outraged citizens’ only remaining recourse was to wait until Election Day in 1934.

But in the mean time, the case of the murder of Lew Nelan was still pending in Tazewell County criminal court.

Completely overshadowed and shoved off the stage during the attempts to prosecute the deputies and remove the sheriff, in the autumn of 1933 the case that had initially sparked these fires of public uproar finally returned to the public’s view.

Next week: The Nelan case goes to trial.