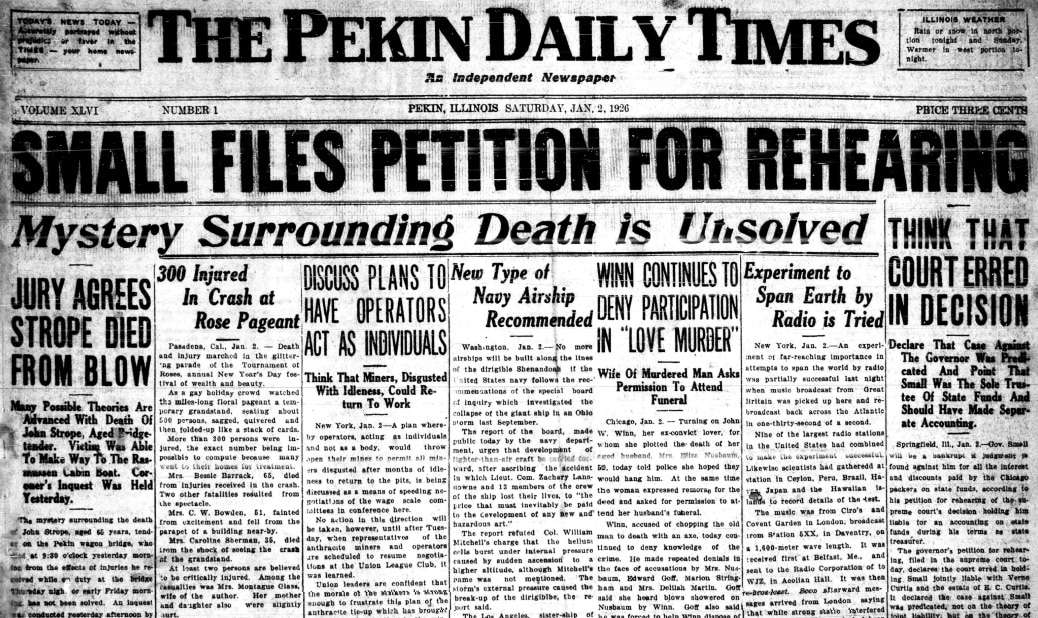

With this post to our Local History Room weblog, we continue our series on a pair of sensational deaths that occurred in Pekin, Illinois, during the Prohibition Era. The Local History Room columns in this series, entitled “The Third Degree,” originally ran in the Saturday Pekin Daily Times from Sept. 15, 2012, to March 2, 2013.

THE THIRD DEGREE

By Jared Olar

Library assistant

Chapter Twenty-one

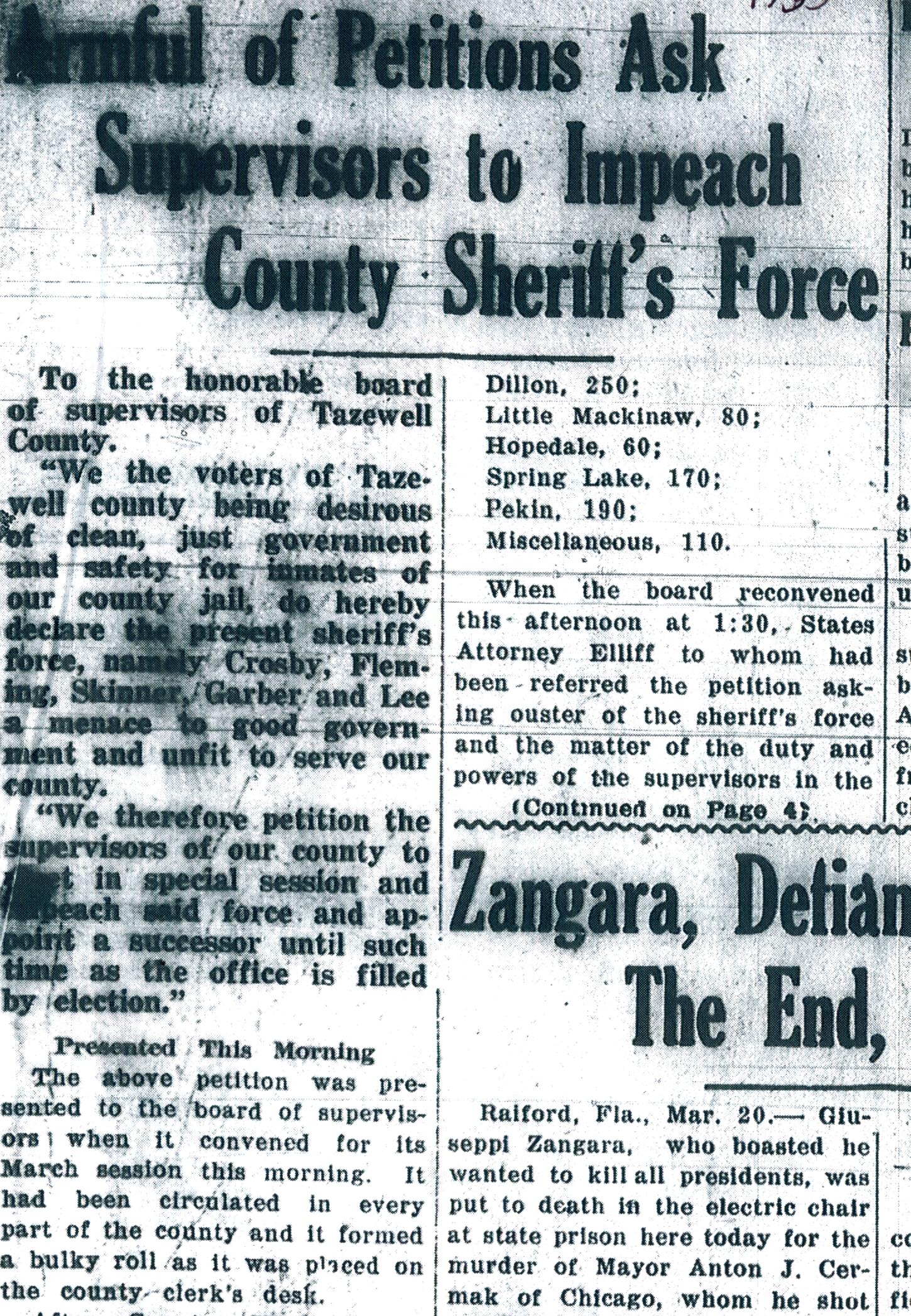

An armful of petitions for impeachment

The manslaughter trial of Tazewell County Sheriff’s Deputies Ernest Fleming and Charles Skinner ended on March 4, 1933, with their acquittal on all charges that they had caused the death of jail inmate Martin Virant. But the controversy surrounding Virant’s shocking death was far from over.

There was, naturally, a lull in news coverage after the jury’s verdict, as the Virant story was immediately pushed off the front page by the death of Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak and the inauguration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Struck by an assassin’s bullet thought to have been aimed at FDR on Feb. 15, Mayor Cermak finally succumbed on March 6.

But before the month was over, the Virant story was back on the front page.

Despite the jury’s verdict, probably the majority of Tazewell County’s residents understandably remained convinced that Virant had died as a result of being tortured by sheriff’s deputies. Their desire for justice remained unsatisfied.

In prior decades, the death of a man as a result of harsh or violent interrogation methods may not have elicited much disapprobation, but by the 1930s attitudes about police brutality were changing.

Pekin Daily Times publisher and editor F.F. McNaughton probably spoke for many in his editorial on the front page of the Sept. 6, 1932 edition, entitled, “THE THIRD DEGREE.” McNaughton took what perhaps most people would have seen as a moderate position on police torture, opining, “Too little third degree is weakness; but too much is outrageous.”

He began by noting that, “Use of the ‘third degree is not confined to Pekin. In the days when my job was to cover police headquarters in New York city I used to cringe as I heard the screams of men being tortured as police sought to wring confessions from them. And I may as well confess to you right now that often I didn’t care how much they were tortured.”

McNaughton defended the use of torture by police as a necessary means of dealing with known, hardened criminals. “Criminals have no qualms in the methods they use,” he wrote. “So you can’t get anywhere by using the methods of a primary teacher on them.

“But,” he continued, “dealing with a known desperate criminal is one thing. Dealing with just you or me is another. . . .

“To slap a man may be all right; or to frighten him; or to keep him awake for hours and days till he becomes too tired to tell anything but the truth is good third degree work, particularly if mixed with clever trapping questioning.

“But if there has been ‘stepping on my neck, kicking me from one side to the other, breaking my ribs,’ and the like as the now mute lips of this dead man testified under oath, the thing has been overdone and the people of Tazewell county who hire and pay the officials demand that a stop be put to it.

“Because a man is foreign born is no reason to treat him as ‘just a damn foreigner.’ . . . They are all human beings and life is dear to them.”

But many people regarded any use of “the third degree” as a grievous violation of an individual’s God-given human rights. To cite one example, in the same week that the Tazewell County grand jury considered the case of Martin Virant’s death, the 109th annual Illinois conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church was under way in Springfield.

During the conference, a resolutions committee report was adopted condemning the employment of “third degree” methods to force confessions from accused prisoners. In his denunciation of police torture, the Rev. J. Williams of Bartonville specifically cited and discussed Virant’s death.

Soon after, at the annual convention of the Tazewell County Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, held at Deer Creek on Sept. 28, 1932, a resolution was passed saying the name of Tazewell County had been put to shame, and condemning “any cruel, brutal, or inhuman treatment in methods being used by its county officers, or its law enforcing body, in third degree methods, to obtain confession or information from suspected offenders, or criminals.” The women sent a copy of their resolution to Sheriff Crosby.

Evidently the sentiment aroused among central Illinois residents by Virant’s death was very strong. Consequently, when Fleming and Skinner were acquitted, some of the outraged citizens in Tazewell County began to look for alternative civil means to obtain the justice that had been denied.

So it was that on March 20, 1933 – just 15 days after the end of the trial of Fleming and Skinner – a group of Tazewell County citizens delivered petitions and a heavy stack of signatures to the Tazewell County Board, calling for the impeachment and removal of Sheriff James J. Crosby and of his entire force.

“To the honorable board of supervisors of Tazewell County,” the petition said, “We the voters of Tazewell county being desirous of clean, just government and safety for inmates of our county jail, do hereby declare the present sheriff’s force, namely Crosby, Fleming, Skinner, Garber and Lee a menace to good government and unfit to serve our county.

“We therefore petition the supervisors of our county to meet in special session and impeach said force and appoint a successor until such time as the office is filled by election.”

Next week: The county board responds.