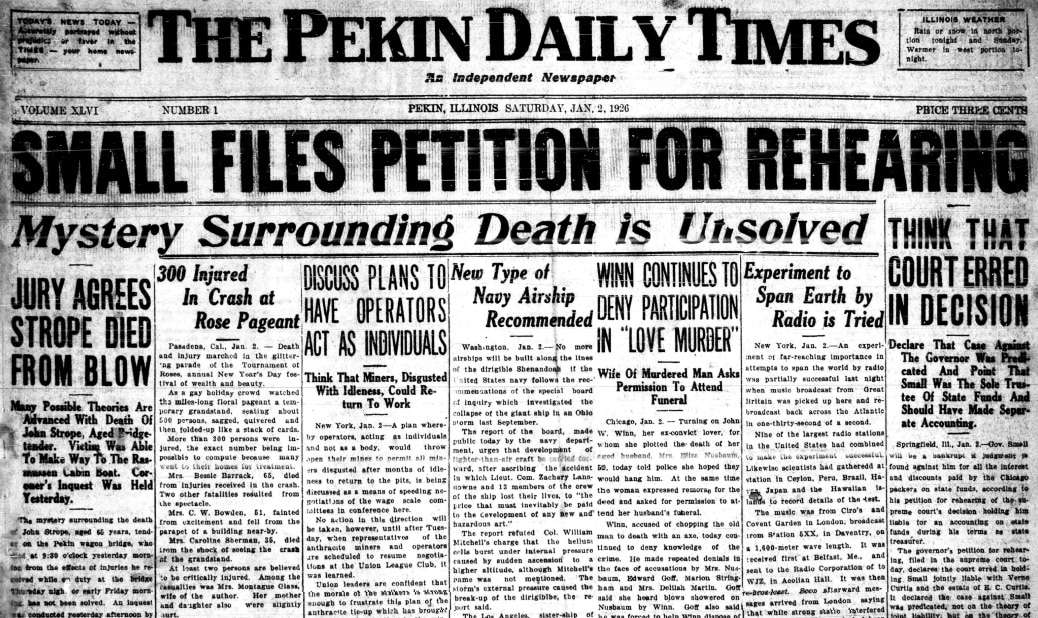

With this post to our Local History Room weblog, we continue our series on a pair of sensational deaths that occurred in Pekin, Illinois, during the Prohibition Era. The Local History Room columns in this series, entitled “The Third Degree,” originally ran in the Saturday Pekin Daily Times from Sept. 15, 2012, to March 2, 2013.

THE THIRD DEGREE

By Jared Olar

Library assistant

Chapter Eighteen

The defense pleads its case

At the end of a long succession of witnesses and physical evidence, the prosecution rested its case on Feb. 26, 1933, in the trial of Tazewell County Sheriff’s deputies Ernest Fleming and Charles Skinner, who were accused of causing the death of Tazewell County Jail inmate Martin Virant by severely beating him during a so-called “third degree” interrogation.

The following day, the defense attorneys Jesse Black Jr. and William J. Reardon began to call their own lengthy list of witnesses and experts, who would help the defense build its case that the deputies never did any violence to Virant, nor did they hang his dead body – rather, the defense contended, Virant had committed suicide. Heading the witness list was J. Hardy Garber, a deputy who helped Skinner bring Virant to and from the Lew Nelan murder inquest.

Garber and the three other deputies involved in this case – Fleming and Skinner, who both took the stand in their own defense, and Frank Lee, originally indicted by the Tazewell County grand jury but whose charges were dropped just before the trial began in Menard County – offered very important testimony.

Presenting a united front, they resolutely denied that anyone had done more than raise his voice at Virant while he was in the custody of the Tazewell County Sheriff’s Department. The four deputies agreed that there had been absolutely no beating or kicking or any kind of rough handling.

The four deputies did state, however, that they noticed Virant had some cuts and bruises about his head and neck when he was first brought to the jail. They denied knowing how Virant had gotten those injuries.

The deputies also agreed that Virant became very frightened and upset, and refused to let them take his fingerprints, after Lee brought in a package containing two metal pipes and unrolled it in Virant’s presence.

Skinner and Fleming also supplied a very important element of the defense’s alternate scenario of Virant’s injuries and death. Flatly contradicting former Coroner A. E. Allen’s testimony that he had eased Virant’s body to the cell floor when he cut his body down, Skinner and Fleming claimed Allen had irresponsibly and unprofessionally let Virant’s body crash to the floor. Virant’s body had even slammed against the toilet as it fell, the accused deputies insisted.

Relying on their medical experts, the defense argued that most of Virant’s bruises and injuries, including his broken rib, were caused when Allen cut his body down and let it crash to the floor. Also backing up this claim were three jail inmates, Charles Cameron, 62, formerly of Delavan, Joe Hensley, and Thomas Davis.

Cameron, a jail trustee, told the jurors, “I saw Allen cut the strap and saw Virant fall on the toilet bowl. He came down awful hard . . . He was dropped. Mr. Allen didn’t touch him. . . . It jarred the whole floor of the cell.” Cameron even claimed that Allen jumped out of the way so Virant’s body would hit the toilet as it fell.

Hensley, another jail trustee, corroborated some of Cameron’s testimony, claiming, “I heard the sound when he was cut down. It came down hard. . . . I heard a loud thump on the iron floor – loud enough to be heard outside of the jail.”

In cross-examination, however, Elliff showed that Cameron’s testimony differed significantly from what he had previously told the Tazewell County grand jury and disagreed with a statement he had made to former Tazewell County State’s Attorney Louis P. Dunkelberg on Sept. 9, 1932.

Cameron responded to Elliff’s questions by disavowing most of his prior statement, and in particular he denied speaking to fellow inmate Elizabeth Spearman. Cameron’s original statements had corroborated key elements of Spearman’s testimony, which supported the state’s case that Fleming and Skinner had beaten Virant.

Some of Hensley’s testimony was especially helpful to the defense’s contention that Virant had committed suicide. Hensley claimed that during Virant’s first night in the jail, Tuesday, Aug. 30, 1932, “I heard the bunk chains rattling and then like someone came off the bunk onto the floor. That was after 2 o’clock. Then I heard moaning and groaning. . . . I heard him saying, ‘Poor John, he did I did too.’”

The words Hensley claimed to have heard Virant say, according to the defense, amounted to a confession that he had helped John Petje murder Lew Nelan. A sense of guilt over his role in Nelan’s death was the reason he committed suicide, the defense attorneys claimed.

Davis also testified that he heard noises from Virant’s cell three times that night as of someone jumping off the bunk, including at 2 a.m. and 3 a.m. In addition, Davis claimed to have heard the same kind of noise sometime after 1 p.m. on Thursday, Sept. 1, and to have heard Virant making a noise.

The defense argued that the noises Hensley and Davis said they heard Tuesday night were not the groans of a man who had been severely beaten, but were the sounds of Virant attempting to hang himself using some strings and threads that investigators found in his cell after his death.

The defense attorneys suggested that some of Virant’s injuries may have been caused during this purported first suicide attempt, but they did not try to explain why Virant would have opted first for strings that were unlikely to support his own weight and only two days later decide to use his own belt.

The defense also claimed that Davis had heard the sounds of Virant killing himself on Thursday, Sept. 1.

Or were they the sounds of deputies faking Virant’s suicide?

Next week: The defense rests.

q