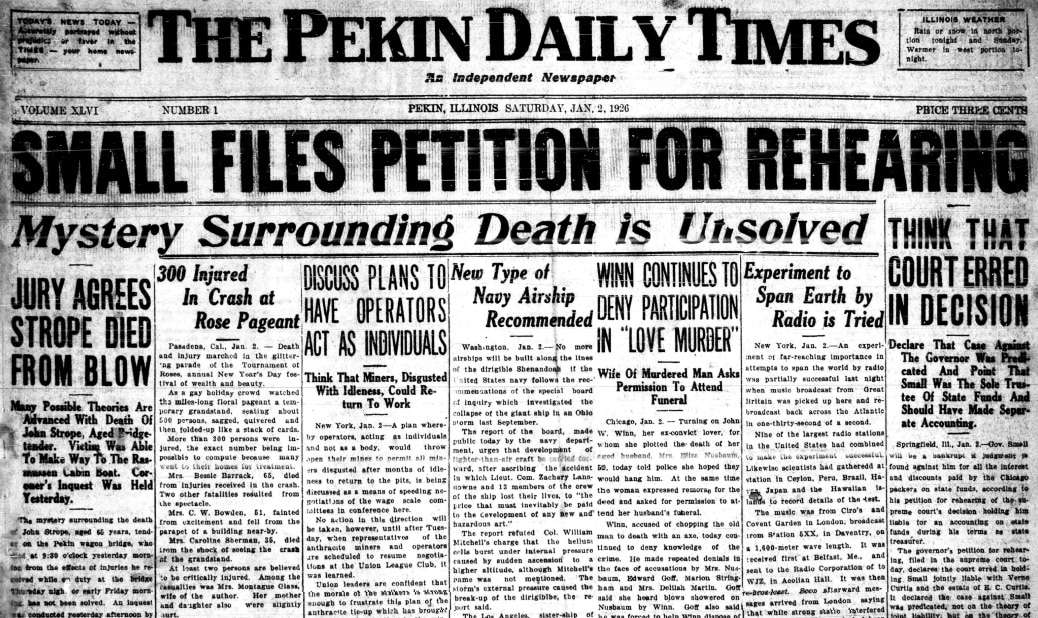

With this post to our Local History Room weblog, we continue our series on a pair of sensational deaths that occurred in Pekin, Illinois, during the Prohibition Era. The Local History Room columns in this series, entitled “The Third Degree,” originally ran in the Saturday Pekin Daily Times from Sept. 15, 2012, to March 2, 2013.

THE THIRD DEGREE

By Jared Olar

Library assistant

Chapter Fifteen

The prosecution painstakingly lays out the case

On Feb. 21, 1933, the first day of the Martin Virant manslaughter trial in Petersburg, Ill., prosecutors began to build their case that Virant, an inmate at the Tazewell County Jail in Pekin, had been brutally beaten by Sheriff’s Deputies Ernest L. Fleming and Charles O. Skinner.

Virant, a potential witness in the Lew Nelan murder case, was found hanging in his cell on Sept. 1, 1932, but investigators and a coroner’s inquest jury found that he was already dead when he was hanged, and that the hanging had been staged to try to cover up the true cause of death.

Many of the same people who testified at the Virant inquest on Sept. 14, 1932, also testified during the manslaughter trial. For example, the first witness for the prosecution was Frank Franko of Peoria, Virant’s brother-in-law, who repeated for the jury what he had previously testified at the inquest.

Next, the jurors heard testimony from Tazewell County Jail inmate Elizabeth Spearman of Peoria, who provided crucial testimony on behalf of the prosecution regarding Virant’s treatment and statements he made, as well as the injuries he suffered while in the custody of the county’s deputies.

Spearman’s testimony was vital to the state’s case, because, on account of Virant being dead, Judge Guy Williams had excluded as inadmissible hearsay the entirety of Virant’s testimony at the Lew Nelan inquest, when a noticeably injured Virant boldly accused Skinner and other deputies of nearly beating him to death.

After Spearman’s testimony, the state called Peoria attorney Vic Michael, legal counsel for the Virant family who was representing them in a wrongful death lawsuit against Tazewell County Sheriff James J. Crosby. On Sept. 1, Michael had accompanied Virant’s sister and Frank Franko to Pekin to get Virant released from jail.

According to the Pekin Daily Times, “Michael related that he had gone to the sheriff’s office in the courthouse and talked to Deputies Skinner and Fleming. Finally Skinner said, ‘Oh, go get the —– out.’ Skinner started to walk across the yard with Attorney Michael and his party following. Then, related Michael: ‘All of a sudden I saw a newspaper man named Watson of the Pekin paper go by on the right. He ran up the jail steps into the jail. I decided something must be up and I followed. The door was shut, but a lady let me in. Dr. Allen was just pronouncing Virant dead after trying to revive him with artificial respiration.’ Michael related that Virant’s right ear was swollen and he had bruises on the back of his head and a hole in the head was bleeding.”

Like Michael, several other witnesses provided testimony establishing that Virant had no visible injuries when he was first brought to the jail on Aug. 30, 1932, and describing Virant’s injuries that they saw at the Nelan inquest or on his dead body. Among those witnesses was Pekin attorney James St. Cerny, who was called to the stand after Michael and who testified that Virant had no visible injuries when he was booked into the jail.

Similarly, in testimony on the second day of the trial, Feb. 22, 1933, Edward Tucker, East Peoria city clerk, George Reichelderfer, superintendent of East Peoria water works, and Charles Schmidt, East Peoria justice of the peace, all said that Virant had no visible injuries when they saw him with Deputy Skinner in East Peoria on Aug. 30. Frank Virant, however, saw his brother’s body at the undertakers on the day of his death, and noticed “a black spot on his left ear that extended down to his jaw,” which obviously could not have resulted from a hanging.

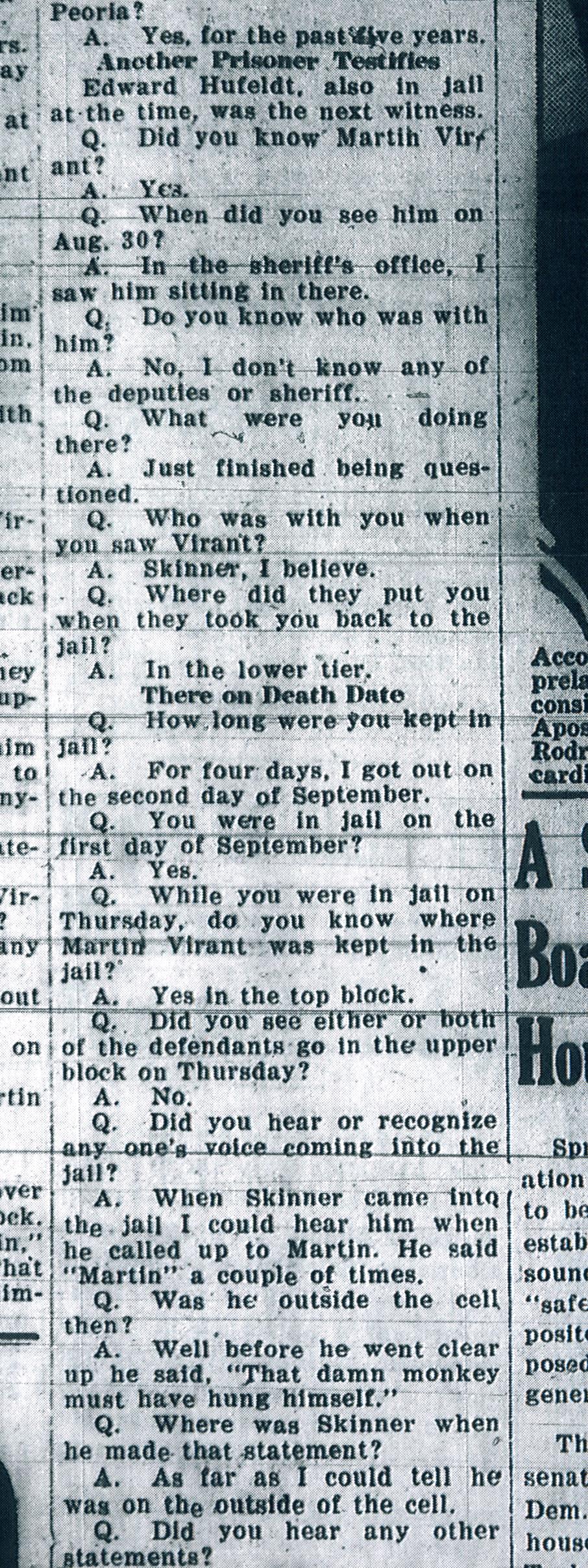

The next to testify was George Genseal, who, like Virant, had been brought to the jail as a suspect in the Nelan murder case, but subsequently was released. He reiterated what he had said at Virant’s inquest, substantiating key points of Spearman’s testimony. After Genseal, Edward Hufeld, one of the defendants in the Nelan case, was called to the stand.

In relating the events of how Virant was found hanging in his cell, Hufeld told much the same story as Genseal. However, Hufeld provided an important additional detail. As the Pekin Daily Times reported on Feb. 22, 1933, Hufeld testified, “When Skinner came into the jail I could hear him when he called up to Martin. He said ‘Martin’ a couple of times. Q. Was he outside the cell then? A. Well, before he went clear up he said, ‘That damn monkey must have hung himself.’”

If Hufeld was remembering truthfully and accurately, this comment would suggest that even before he had ascended the stairs to the upper tier of cells, Skinner already knew he would find Virant dead and hanging.

On the third day of the trial, Feb. 23, the state called H. A. McCance, jury foreman at the Nelan inquest, and asked him to describe Virant’s appearance and demeanor during the inquest. Though Virant’s testimony at the inquest was inadmissible, McCane still was able to tell the jury that Virant appeared to be in pain or distress, and that his face appeared to be in misery.

Also called to describe Virant during the Nelan inquest was Janese Shipley, stenographer at the Nelan inquest. She testified that Virant had two black eyes, a swollen ear and blood on his shirt shoulder, and that Virant spoke in a voice that was “louder than an ordinary person.”

As the trial continued, the state made its way down its lengthy list of witnesses, methodically and painstakingly – and at times tediously – laying out its case for the deputies’ guilt.

But thanks to defense attorney Jesse Black Jr. of Pekin, the trial proceedings never stayed boring for very long.

Next week: The courtroom theatrics of Attorney Black.