Here’s a chance to read again one of our old Local History Room columns, first published in March 2012 before the launch of this blog . . .

In his 1879 Tazewell County history, Charles C. Chapman observed – perhaps with his tongue implanted in his cheek – that, “as immaculate and good as the pioneer fathers undoubtedly were, even among them there were wicked and vicious characters.”

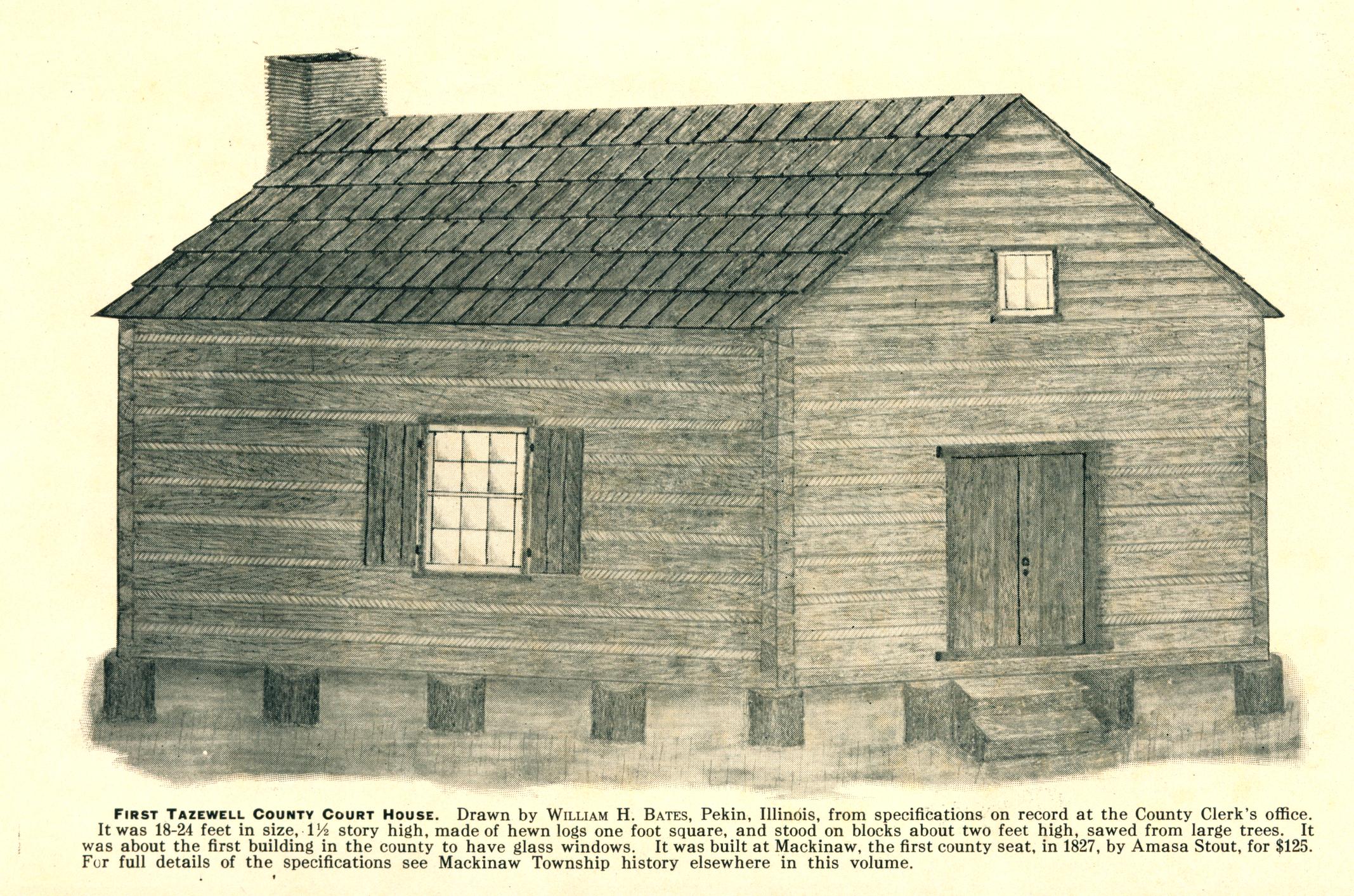

Crime called for punishment and incarceration of evildoers, so on June 28, 1828, the county contracted for the building of a jail at Mackinaw (then the county seat), at a cost of $325.75, which was three times what the county had paid for its Mackinaw courthouse. “It was,” Chapman says, “a two-story structure, 16 feet square, made of solid hewn timber, and was one of the strongest and most costly jail building erected by the pioneers throughout Central Illinois. Nevertheless, the very first prisoner incarcerated within its heavy walls took flight the same night. This individual, whose name was William Cowhart, is also noted for being the first horse-thief in Tazewell county.”

After the return of the county seat to Pekin in 1848-49, new county buildings were constructed. The new Tazewell County Jail, “calculated to hold from fifteen to twenty prisoners, was built by the Board of Supervisors of Tazewell County, in 1852, at a cost of $7,000,” says the 1870 Pekin City Directory.

Besides the county jail, the Pekin city police had their own lockup, quaintly known as “the calaboose.” The 1870 City Directory informs us, “The first calaboose was contracted for in November, 1849, John S. Boone being the contractor, and the cost of the building limited to forty-eight dollars. This building remained the city lockup until the summer of 1868, although it was long considered, especially by evil-doers, a noisesome, pestilential nuisance. In the latter years it was destroyed by fire, the incendiary work of some transgressors confined within its walls.”

Not every malefactor ended up in the city calaboose or county jail, of course. The usual penalty would be a fine. Chapman says it was in 1829 that the county received its first fine for a violation of the peace. That was a case in which Isaac Storms had assaulted James Brown. Chapman comments, “For many years the only cases before the justices of the peace were for assault and battery,” showing the “Wild West” character of Pekin and Tazewell County in those days.

Then as now, more serious crimes would lead to imprisonment, and murderers often would find their terms of imprisonment ended at the hangman’s gallows in Pekin’s courthouse square. The first murder indictment in Tazewell County, according to Ben C. Allensworth’s Tazewell County history, was handed down against John Wood, who was sent to prison for four years for killing his own child “by throwing it up against the ceiling.”

The first public execution in Pekin was March 1, 1861. On Oct. 12, 1860, John Ott decided to burglarize George W. Orendorff’s home about four miles southeast of Delavan. George was away on business that day, but finding the mother and her two daughters, Emma, 9, and Ada, 7, at home, Ott cold-heartedly murdered them with an axe. On the day of Ott’s hanging, a carnival atmosphere had formed as about 10,000 people crowded downtown to watch his execution, and three companies of soldiers were brought from Peoria to prevent a lynching.

The 1974 Pekin Sesquicentennial says, “Ott, reports indicate, remained calm throughout the entire affair, and just before falling through the trap of the scaffold declared that he alone was guilty of the crime for which he was about to die (a man named Green” – that is, Ott’s cousin Enoch Green – “had been arrested also), that his doom was just, and that he hoped to be forgiven in Heaven, where he hoped to meet those who were there to witness his death. He muttered a prayer as the trap fell; his neck was broken by the fall; but he hung for 19 minutes before being cut down and placed in a coffin.”

Not all hangings resulted from due process of law, however. Perhaps better known than Ott’s execution is the 1869 lynching of William Berry, leader of the Berry Gang, as related in local historian Jim Conover’s book, “Lynch Law.”

The last legal hanging in Pekin was March 14, 1896. Albert Wallace of Delavan was put to death for murdering his sister and severely wounding his sister’s husband. Showing no remorse, Wallace reportedly said just before his hanging that someday “these people will be sorry for what they are doing.” It is not recorded whether they ever regretted his execution, however.