In this column we explore topics related to the history of Pekin and Tazewell County during the period of the past two centuries or so. This week, we’ll take a look at a remarkable matter of natural history having to do with one of our area’s natural, primeval features: the Mackinaw River, an important tributary of the Illinois River.

Water has probably flowed down the Mackinaw into the Illinois River far longer than anyone can imagine. The river’s source is far to the east, near the village of Sibley in Ford County, and it then meanders and wends its way for about 130 miles through McLean, Woodford and Tazewell counties.

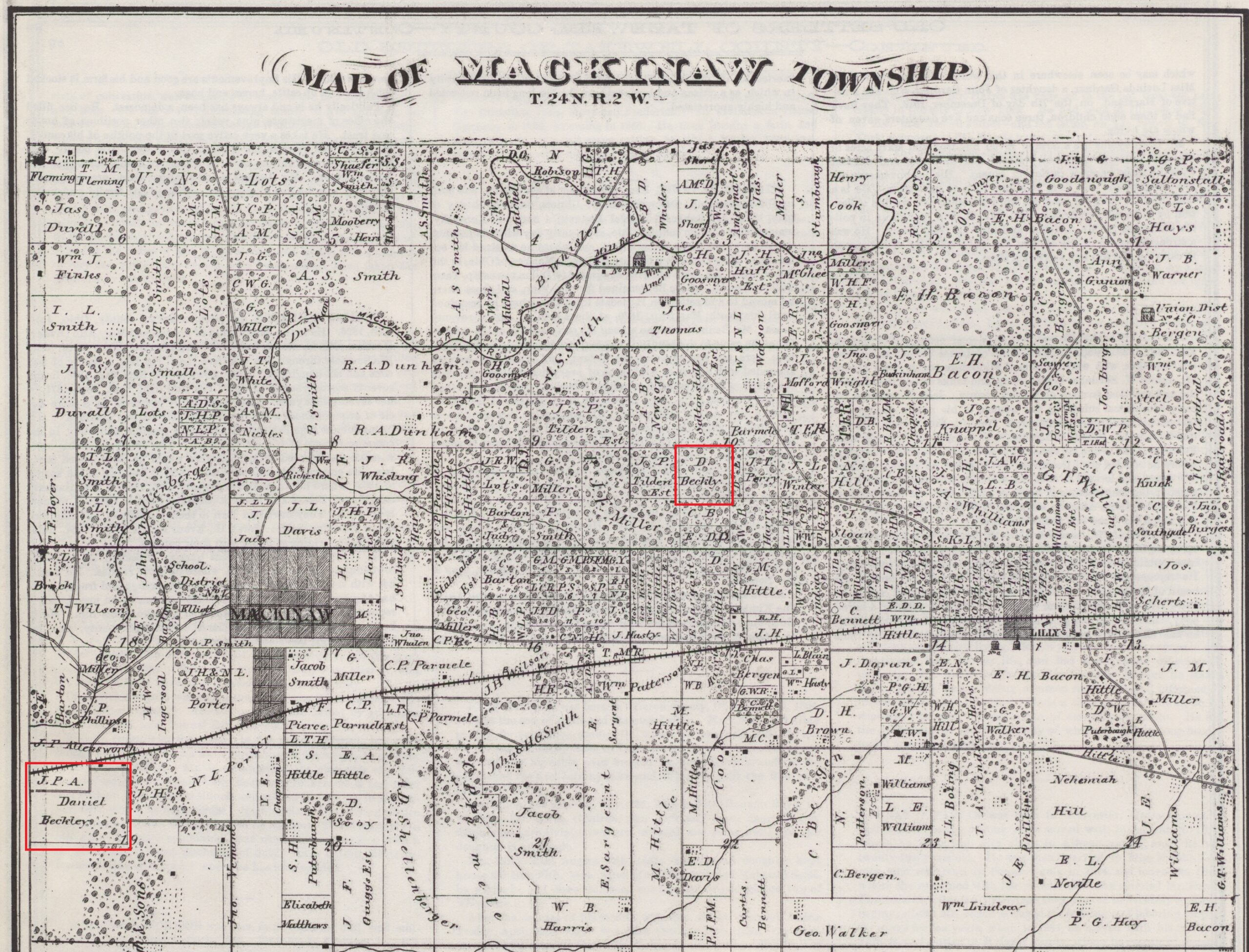

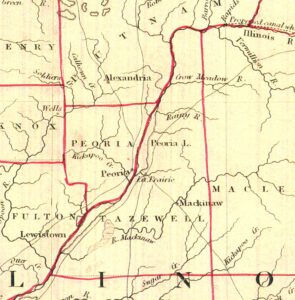

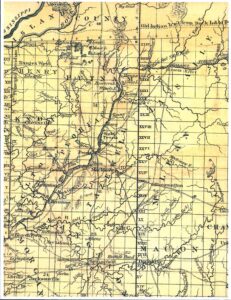

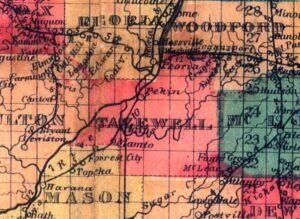

However, a survey of old maps and atlases reveals that the Mackinaw River’s outlet was not always where it is today. The river formerly flowed through what it now Mason County, but, as David Perkins of the Tazewell County Genealogical & Historical Society recently brought to my attention, at some point between the 1830s and 1860s, the Mackinaw shifted its course. No longer did the Mackinaw River continue a generally westward course until emptying into the Illinois in Mason County near the spot where Chautauqua Lake is located today. Instead, the Mackinaw took a northward turn and found a new outlet at a location on the Illinois just west of the modern-day Powerton Fish and Wildlife Area.

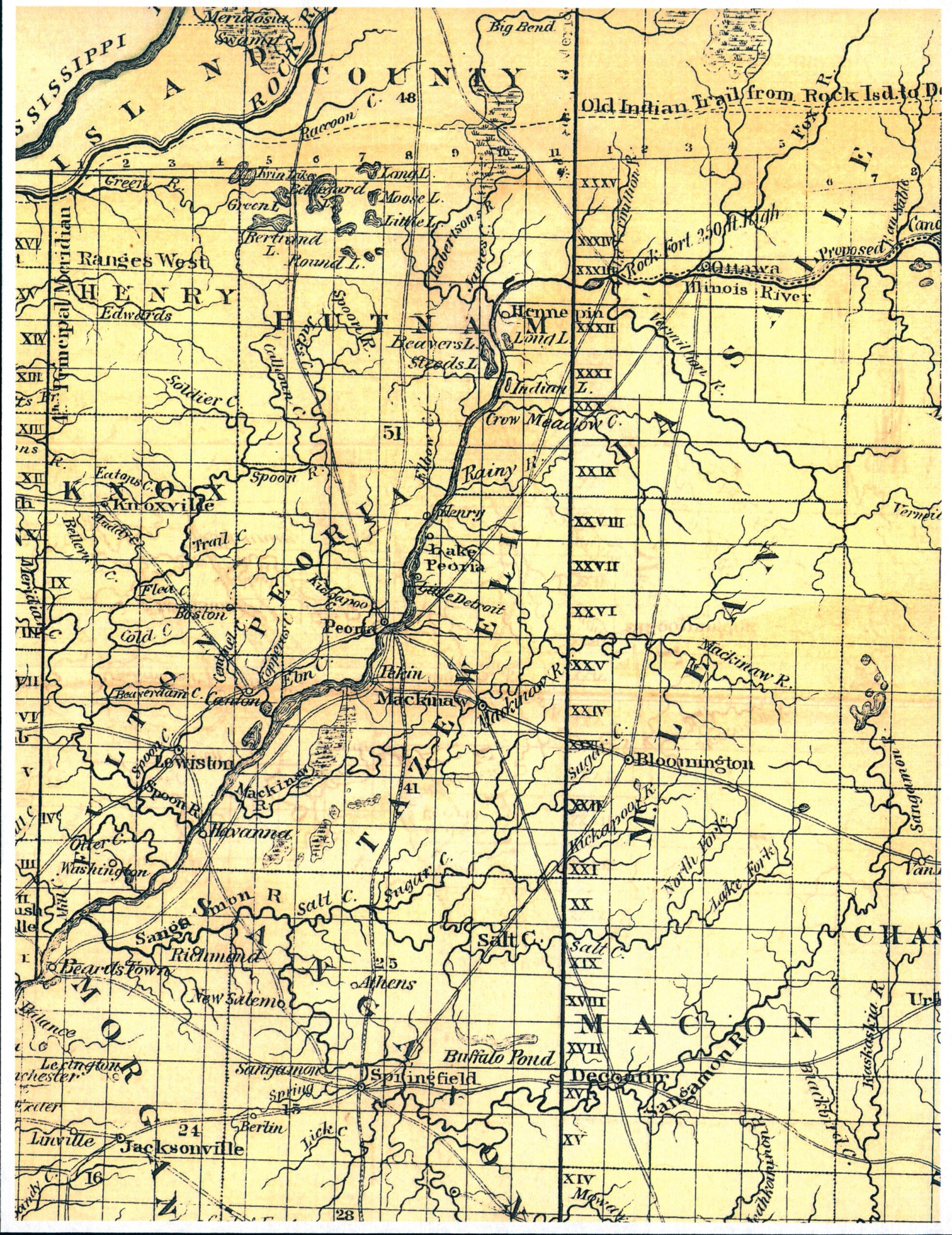

Early Illinois maps and sources document the old course of the Mackinaw River. An 1815 map by Rene Paul (Plate XL in “Atlas: Indian Villages of the Illinois Country 1670-1830), for example, shows the “Macanac R.” flowing west-south-west into the Illinois River at a point nearly opposite the mouth of the “La Marche” river, a good ways south of Peoria Lake. No northward bend in the Mackinaw is shown.

Another early publication, Zadok Cramer’s 1808 “The Navigator,” reprinted in 1818 and excerpted in the July 2009 Tazewell County Genealogical & Historical Society Monthly, describes the “Sesemi-Quain” and “De la March” rivers, tributaries of the Illinois, before coming to:

“The river Michilimackinac, comes in on the south-eastern side, above the two just mentioned, and 195 miles from the Mississippi; it is navigable 90 miles, 50 yards wide, and has at its mouth 30 to 40 small islands, which at a distance look like a small village. Some distance up this river is a coal mine, on the banks are red and white cedar, pine, maple walnut, & c.”

“Michilimackinac” was the full, original name of the Mackinaw. But the distance of “195 miles from the Mississippi” does not accord with the course and length of the Illinois River today. A 1998 edition of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ “Illinois Waterway Navigation Charts” shows the present mouth of the Mackinaw at about 148 miles upriver from Grafton, Ill. (which is where the Illinois joins the Mississippi River today), while the former mouth of the Mackinaw River was at a spot approximately 124 miles upriver from Grafton.

An 1819 map of Illinois by John Melish (Plate XLVI in “Atlas: Indian Villages of the Illinois Country 1670-1830), presents the “Michilimackinac R.” flowing much as Rene Paul’s 1815 map shows the “Macanac R.” The same basic water course for the Mackinaw can be found on an old 1822 atlas map. Baldwin & Cradock’s 1833 atlas also shows the mouth of the Mackinaw far to the south of its present mouth – but significantly, this atlas map illustrates that before it found the Illinois, the Mackinaw flowed into an extensive swamp in what was then Tazewell County but is today Mason County. This old swamp bears on the changed course of the Mackinaw.

A map obtained by David Perkins, formerly a plate illustration in an 1879 book, shows northern and central Illinois in 1835. This map also shows the old swamp, but traces the course of the Mackinaw along the southern boundary of the swamp. Notably, however, the map also shows a stream or rivulet along the swamp’s western boundary, running in a generally northerly direction up to the Illinois River at a spot near the present mouth of the Mackinaw.

It appears that around the mid-1800s some local event or events of a geologic nature – say, a flood, perhaps with agricultural activities in or near the swamp being a contributing cause – led to the Mackinaw River shifting its course. Abandoning its former course, the river was diverted, or diverted itself, into the channel of the northerly stream. Henceforth the Mackinaw no longer would flow through Mason County. Thus, an 1864 plat map of Tazewell County shows the Mackinaw following its present course, and all subsequent atlases and maps show the same river course.

While such changes are remarkable, it’s well known that rivers can and do change their courses, whether in slight or major ways. The change in the Mackinaw River’s course no doubt was noticed and recorded by contemporaries, but as yet Perkins and I have found no historical notices of the change. Charles C. Chapman’s 1879 “History of Tazewell County” makes no mention of it, nor do the historical essays in the 1873 “Atlas Map of Tazewell County” say anything about a change in the Mackinaw’s course. More recent reference works that we’ve consulted also are silent on this point.

The Mackinaw’s former course through Mason County still exists, and it even links up to the Mackinaw north of Townline Road in Tazewell County. At that point, one finds a drainage ditch that follows the line of Schuttler Road and then turns straight south along Dinky Ditch Road. Along the way south, it becomes Hickory Grove Ditch, flowing under Hickory Grove Road just east of Manito.

The ditch then makes an eastward curve before swinging diagonally southwest through Mason County – this stretch of the watercourse is known as North Quiver Ditch, but further on past Forest City, it’s the Mason Tazewell Ditch, until finally, past Topeka, it becomes Quiver Creek, which empties into the Illinois at Chautauqua Lake.

But once, way back when, it was the final western length of the Mackinaw River.