This week we revisit the first military engagement of the Black Hawk War of 1832, the Battle of Sycamore, more commonly remembered as Stillman’s Run or Stillman’s Defeat, which took place at a location about midway between Dixon and Rockford in Ogle County. It was in Stillman’s Run on May 14, 1832, that Pekin co-founder Major Isaac Perkins lost his life.

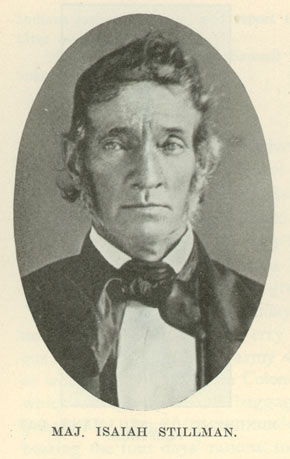

The early publications on Pekin and Tazewell history usually refer to Isaac as “Major Isaac Perkins.” Genealogical researchers of the Perkins family suggest that he probably acquired that rank from an otherwise unknown tour of duty with the Illinois State Militia. Isaac’s only recorded military service, however, was as a Private in the Black Hawk War, when he served in the 5th Illinois Regiment Brigade of Mounted Volunteers under the command of Major Isaiah Stillman, from Fulton County, and Major David Bailey of Pekin.

Charles C. Chapman included an account of the battle on pages 258-261 of his 1879 “History of Tazewell County.” Chapman relates that Stillman and Bailey and their men unwittingly made camp near Black Hawk’s warriors. Stillman’s ill-trained and undisciplined men were immediately thrown into a panic and complete disarray, and the battle, such as it was, quickly became a chaotic retreat (hence the mocking name, “Stillman’s Run”). Black Hawk’s warriors easily slaughtered, scalped and beheaded the few soldiers – about eight or nine men – who attempted to make a stand, including Perkins.

Coming upon the gory scene the next day was a state militia brigade led by a 23-year-old captain named Abraham Lincoln, who with his men gathered the remains of the fallen and buried in a common grave at the battle site, near a creek that consequently was named Stillman’s Creek. In 1901, a monument was erected at the site, which today is at the east end of the town of Stillman Valley.

In addition to Chapman’s account of Stillman’s Run, the Pekin Public Library’s Local History Room collection includes a few other publications pertaining to Illinois history that provide information on this battle. The most detailed and useful of these publications is “Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society for the Year 1902,” which includes papers and talks presented during the society’s third annual meeting in Jacksonville.

Also included, on pages 170-179, is the text of an extended historical address that Illinois historian Frank E. Stevens, author of a work entitled “The Black Hawk War,” presented at the June 11, 1902 dedication ceremonies of the Stillman Valley Monument commemorating the men killed there in 1832. Stevens’ address incorporated or quoted from various eyewitness and contemporary accounts of the battle, including Major Stillman’s own version of what had happened, as published in the July 10, 1832 edition of the Missouri Republican. According to Stevens, though, the debacle of Stillman’s Run was simply a case of panic sweeping through a troop of untrained and undisciplined men.

“After five miles’ pursuit,” Stevens said, “the Indians abandoned it to return to mutilate the bodies of the dead, as described by Mr. [Oliver W.] Hall; but the whites continued their flight, running, riding, yelling, crying – hopelessly crazed, until Dixon’s Ferry was reached in the early hours of the morning of the 15th. Others becoming confused deflected to the south, and never stopped until the Illinois river was reached at a point near the present city of Ottawa. From there about 40 of them scattered for their homes.

“It was a clear case of panic. Men were crazed. They who in a sober moment would have walked straight to death without a protest; they who would bend to no command of a superior officer; they who would not obey or follow, were driven as easily as a flock of panic stricken sheep. It has been said and written that whiskey was the cause of that unfortunate rout; but that assertion is hopelessly improbable in the face of the fact that but two casks were taken with the baggage train to be consumed by 275 men, who lived in a whiskey drinking age, when five or ten drinks, more or less, made little difference in a daily average. Mr. John E. Bristol, of Eads’ company, who at 91 is alive and hearty today, vouches for the truth of this assertion, and the other one, that but two small casks were taken along. Mr. Hall specifically states that one cask was emptied by the Indians, and Black Hawk makes the same statement. Therefore it is certain that whiskey cut no figure in the panic.”

See also “The life and death of Major Isaac Perkins“