This is a reprint of a “From the Local History Room” column that first appeared in Feb. 2015, before the launch of this weblog.

In Ben C. Allensworth’s 1905 “History of Tazewell County,” a former local judge named A. W. Rodecker was asked to write an essay on the history of the legal profession in the county. Rodecker’s essay, on pages 878-880 of Allensworth’s history, is entitled “Bench and Bar” and sketches the general shape of the legal practice in Tazewell during the county’s early years.

Rodecker began with an acknowledgement of the Judaeo-Christian foundations of Western civilization that then informed the practice of law and the functioning of the courts in America. Rodecker commented, “. . . it is true that, in the courts of the country, the Decalogue is recognized as the guide, and as embracing all law and all equity. If a law-making power declares an act to be a law which contravenes the law ‘thundered from Mount Sinai,’ it cannot be enforced, but is null and void.”

Of Tazewell’s first attorneys, Rodecker said, “The lawyers of Tazewell County who came here, or grew up here in an early day, were of the kind who hewed out their way over the roughest road, and blazed it with the glory of well-earned success. They had few books from which to learn, and few decisions of the courts to guide them to settle disputes that grew up in the new State. They fell back upon the old text-books, and became well grounded in principles, and were by no means ‘case lawyers.’ They knew the reason for every rule, and backed up their opinions with a familiarity that was almost invincible. Their knowledge of common law pleadings had to be almost perfect. There was no great code of practice, no very helpful books of forms. They had to plead ‘on the spot.’ A continuance meant costs to their clients, and cases were not then ‘won by delays’ and procrastination. Even on the criminal side of the court, indictments and pleadings did not indulge in a waste of words.”

To illustrate how indictments and pleadings in those days “quickly came to the point,” Rodecker copied an indictment that had been “drawn” in September 1837 by Stephen A. Douglas, who later served as senator for Illinois, but who was then Tazewell County’s interim state’s attorney. The indictment, which Douglass brought before a grand jury, but which the grand jury declined to endorse, said:

“The grand jurors chosen, selected and sworn, in and for the County of Tazewell, in the name and by the authority of the people of the State of Illinois, upon their oaths present that Clark Kellogg, on the twenty-seventh day of May, in the year of our Lord, One Thousand Eight Hundred and Thirty-Seven, at the county aforesaid, one bay mare, of the value of Fifty Dollars, of the goods and chattels of one Joseph Kelso, in the peace, then and there being found, unlawfully, and feloniously, did steal, take away, and drive away, contrary to the statute in such case made and provided, and against the peace and dignity of the same people of the State of Illinois.”

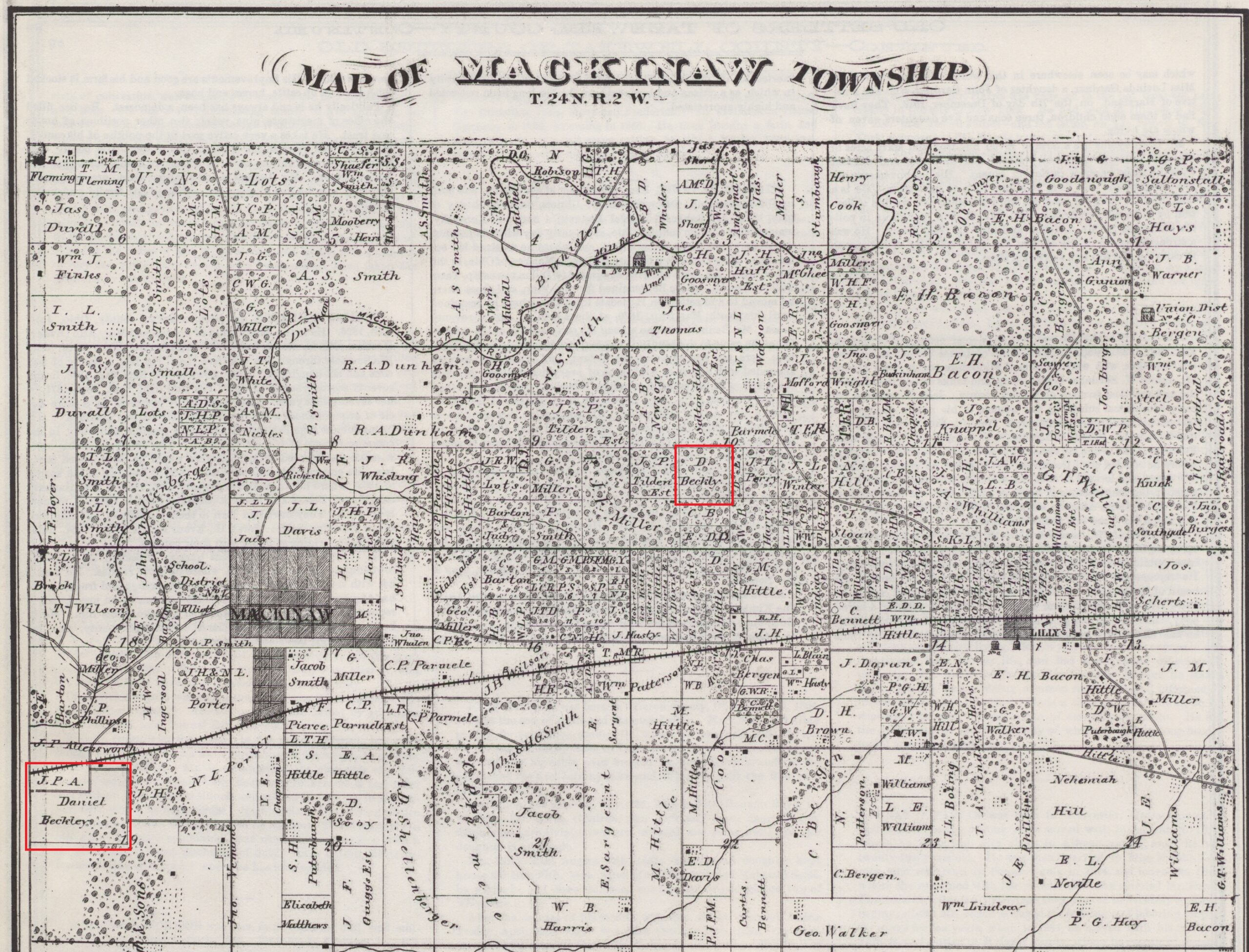

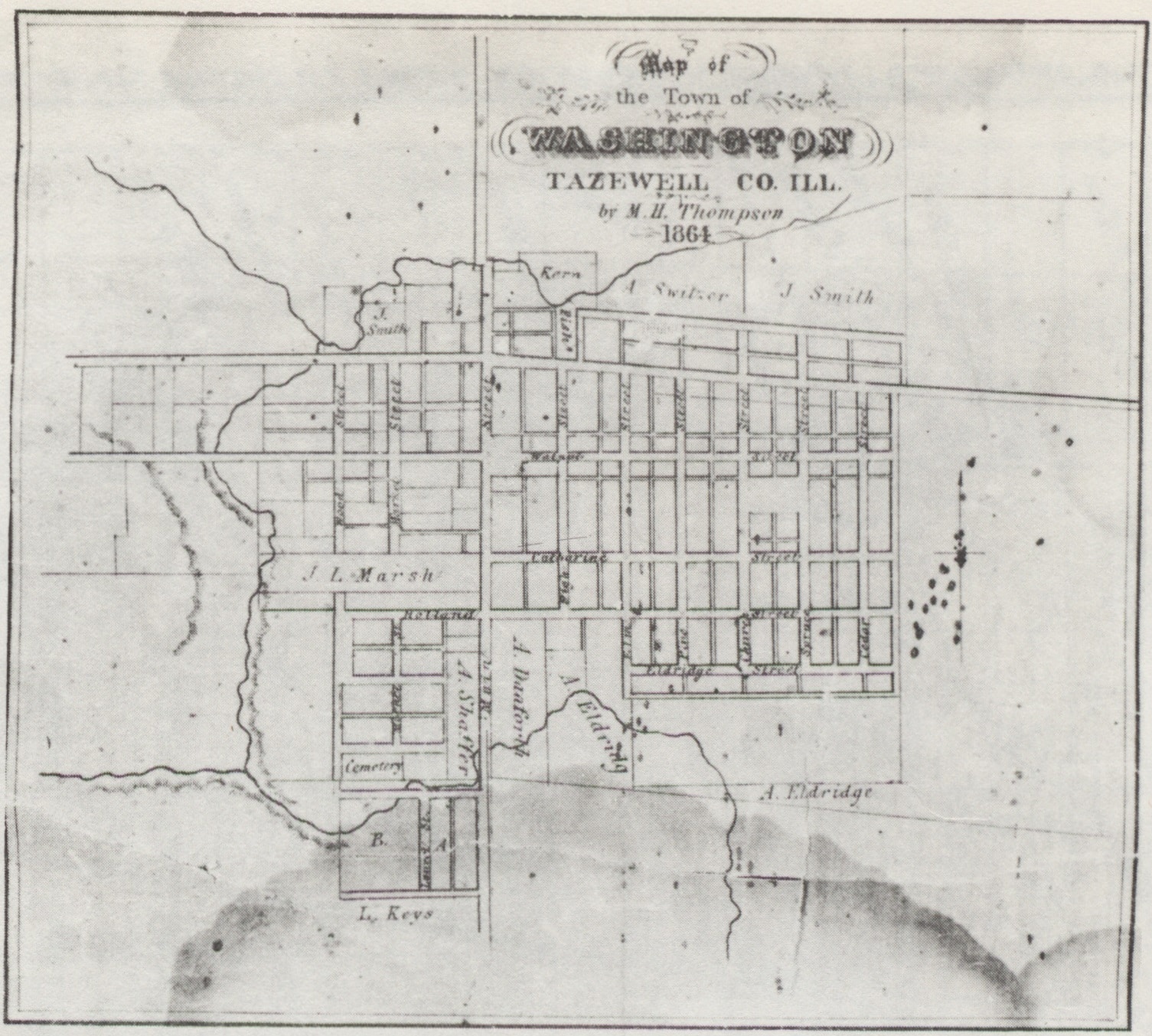

Rodecker’s essay then tells of how the first term of the circuit court in Tazewell County was convened in Mackinaw, the county seat, on May 12, 1828, with Samuel D. Lockwood as the presiding judge. “The first common law case was one of debt, and the first criminal case was for assault and battery,” Rodecker said.

Continuing, Rodecker said, “In 1831 the county-seat was moved from Mackinaw to Pekin, and court was held in what was then known as the Snell School House, which was situated on the west side of Second Street, between Elizabeth and St. Mary’s Streets. In 1826 it was moved to Tremont . . . In 1850 the present court house was completed, and, in August of that year, the county-seat was again moved to Pekin.” That was the court house building that preceded the current Tazewell County Court House.

Rodecker was evidently pleased to be able to boast in 1905 that “Not in all the years of Tazewell County’s existence has a member of its bar been convicted of a crime, or been disbarred for unprofessional conduct” – something that can no longer be said today.

After an enumeration of the county’s attorneys and judges, Rodecker told the following anecdote of swift justice concerning Judge Charles Turner, who had served as a colonel and brevet brigadier general during the Civil War:

“He was a fearless man in every emergency. I well remember that his courage was put to a strong test while he was Judge of the Circuit Court. One night, after he had retired, he heard a noise in the basement of his house, and he got out of bed to investigate and found that his home was being burglarized. He caught sight of a man stealthily creeping from room to room. The Judge as quietly crept after him, and when, in reaching distance, pounced upon him. The burglar was armed with an iron poker, and a terrible fight followed. First the Judge was on top, and then the burglar; but the Judge proved the more powerful man, and, although the burglar was a desperate fighting, the Judge soon had him at his mercy. By this time some of the female members of the family came to his aid with lights, and he bound the burglar, and marched him off to jail. The Grand Jury was in session, and the next day the burglar was indicted, and a Judge from an adjoining county called to hold court; the man plead[ed] guilty and was sentenced, and the following day sent to the penitentiary.”