Previously in our ongoing Illinois Bicentennial series, we saw how the controversy over slavery affected the history and development of Illinois from the formation of the Northwest Territory in 1787 right up to Illinois statehood in 1818. In fact, the dispute between Illinois’ pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers played a role both in the breaking off of the Illinois Territory from the Indiana Territory in 1809 and in the race to achieve statehood for Illinois prior to Missouri.

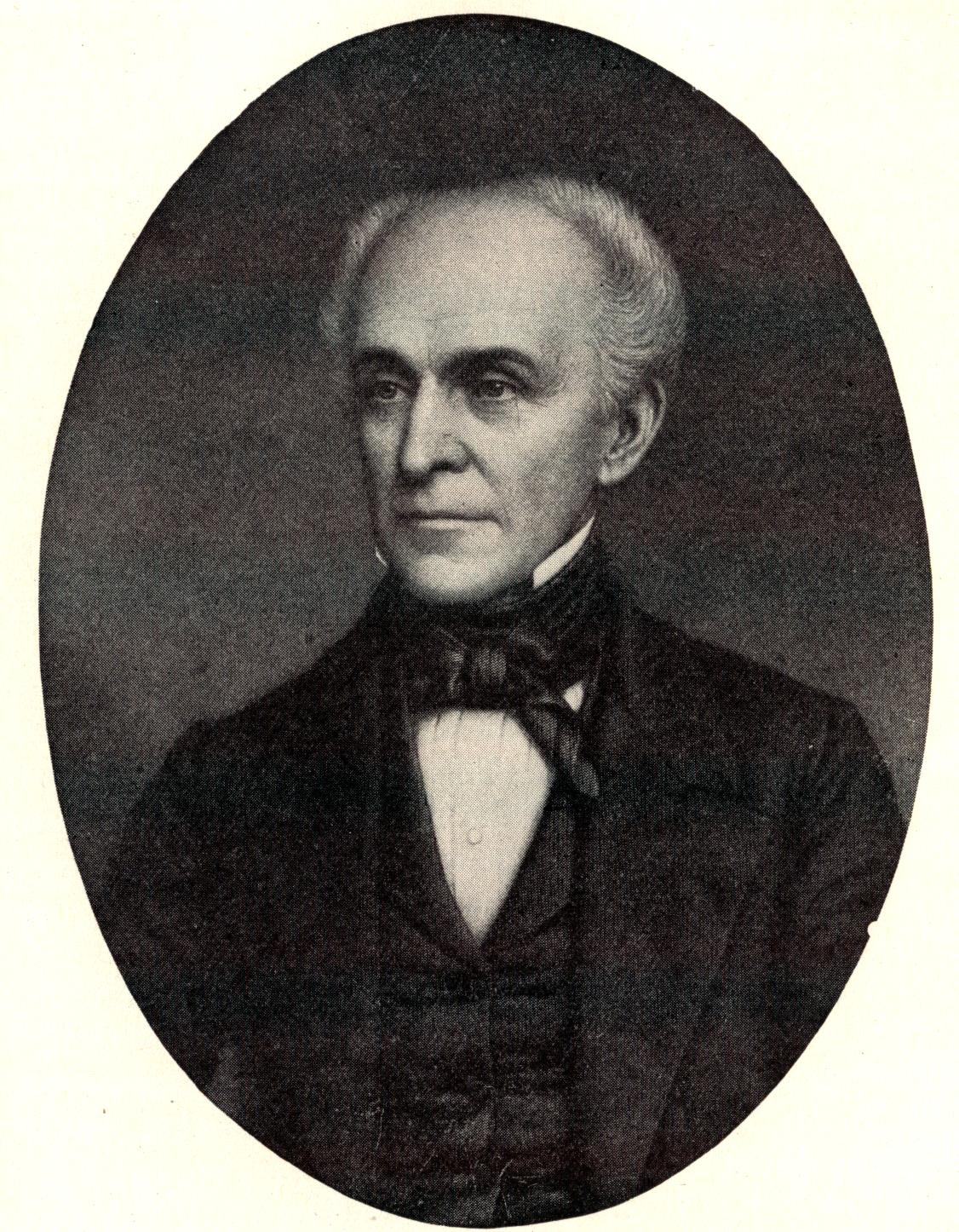

This week we’ll recall how the issue flared up again during the tenure of Illinois’ second state governor Edward Coles (1786-1868).

About two years after Illinois became a state, the U.S. Congress agreed to admit Missouri and Maine to the Union simultaneously under the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which sought to defuse tensions between America’s pro-slavery and abolitionist parties by keeping the numbers of new “slave states” and “free states” balanced. The Missouri Compromise stipulated that slavery would be illegal in any new states formed from the areas of the Louisiana Purchase north of Parallel 36°30′ North.

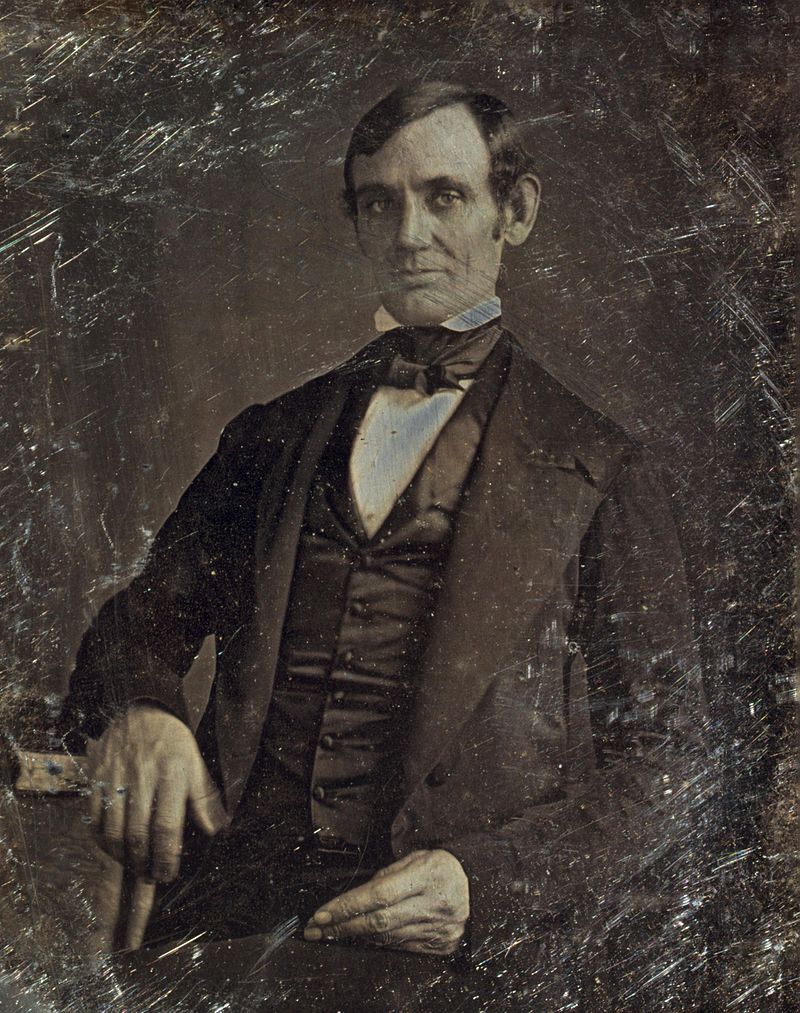

Looking ahead, we can see that although the issue of slavery continued to simmer in the next three decades, at the national level the Missouri Compromise had moved the issue to the back burner. This arrangement endured until 1854, when Congress passed Illinois Sen. Stephen A. Douglas’ Kansas-Nebraska Act, which repealed the Missouri Compromise and made slavery possible north of Parallel 36°30′ North.

Douglas’ rival Abraham Lincoln sharply criticized the Kansas-Nebraska Act in his Peoria speech on Oct. 16, 1854, an important step on the road that would take Lincoln to the White House. The resulting outrage over the act on the part of the free states and the abolitionists led to the dreadful violence of “Bleeding Kansas” and, ultimately, to the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 and the final abolition of slavery in 1865.

In the great conflict over slavery, Illinois was ranged with the free states. As noted before, Article 6 the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had outlawed slavery in any territories or states that later would be formed from the Northwest Territory. But in its early history Illinois’ place among the slave states was somewhat dubious and precarious. Most of Illinois’ early settlers came from slave states and territories, and from 1796 to 1806 there were repeated attempts to legalize slavery in the Indiana and Illinois territories.

Although the pro-slavery forces in Illinois failed to legalize slavery, effectively the practice of slavery still went on in Illinois due to an indentured servitude law that made it possible for slave owners to pressure their slaves to agree to continue to serve their masters after coming to Illinois. In Jan. 1818, the Illinois Territorial Legislature sought to emphasize to Congress that Illinois would be a free state by approving a bill that would have reformed labor contracts to eliminate the practice of indentured servitude. However, Gov. Ninian Edwards (1775-1833), himself a wealthy aristocratic slave-owner, vetoed the bill, claiming it was unconstitutional – the only time Edwards ever exercised his veto power as territorial governor.

After Illinois achieved statehood, pro-slavery forces continued to strive to legalize it. In anticipation of Illinois’ admission to the Union, the territory framed a state constitution in Aug. 1818 – but it is significant that Illinois’ first constitution had a “loophole” of which pro-slavery leaders soon tried to avail themselves in order to legalize slavery. On the question of slavery, the 1818 constitution said, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall hereafter be introduced into this state otherwise than for the punishment of crimes.”

In his 1933 history, “Illinois: the Heart of the Nation,” former Ill. Gov. Edward Dunne explained the loophole in Illinois’ first constitution in these words (pp. 240, 260, 262, emphasis added):

“The section of the constitution relative to slavery and prohibiting it in the state, as amended and finally passed, was a compromise between the pro-slavery and anti-slavery members of the convention. In effect, it practically admitted that the former indentured laws of the territory practically amounted to slavery, but provided that the children of indentured persons were to become free. Under that provision, no indentures made outside the state could be enforced within the state, but the constitution failed to bind the state not to make a revision of the constitution which would admit slavery. Notwithstanding that the constitution failed to have any provision in strict accordance with the Ordinance of 1787 relative to slavery, it was accepted and approved by Congress, . . .

“Slavery had already been introduced into the state. Slaves and indentured servants, who were in almost as abject a condition of service as slaves, were numerous in Illinois at the time this constitution was adopted and, noting the word ‘hereafter’ in the constitution, there was a rush to have indentured articles approved before the constitution went into effect. . . .

“To have framed a constitution favoring slavery, or one making no declaration on the subject, would have invited a denial by Congress of the application for statehood. Therefore, some declaration against slavery was necessary, but reserving a method of reopening the question, was devised and carried in the convention . . . .”

As expected, Dunne wrote, “That opportunity soon arose and was promptly seized by the pro-slavery element in the state.”

It happened following the election of Virginia-born Edward Coles as Illinois’ second governor. In Virginia, Coles held a large estate and owned at least 20 slaves, and he served as President James Madison’s private secretary from 1809 to 1815 with a special assignment as ambassador to Russia. By 1814, Coles had come to oppose slavery, corresponding with ex-President Thomas Jefferson on the subject that year.

After returning from his diplomatic work in Europe, Madison appointed Coles registrar of the federal land office in Edwardsville, Ill. After arranging matters at his Virginia estate, Coles struck out west for Illinois. On the way down the Ohio River, Coles made the decision to set his slaves free. “He promised them each emancipation from slavery,” Dunne wrote, “and 160 acres of land and help for farming, and they, of course, joyfully accepted their freedom and every one of them agreed to accompany him to Edwardsville. Before landing in Illinois Coles gave each of his slaves a written certificate of freedom and all settled around his home near Edwardsville.”

Two years later, Coles and three other men entered the race to succeed Shadrach Bond as governor of Illinois. The other gubernatorial candidates were Illinois Supreme Court Justice Joseph Phillips, Associate Justice Thomas C. Brown, and Gen. James B. Moore – Phillips and Brown ran on pro-slavery platforms, while Coles and Moore were anti-slavery. Even though pro-slavery voters outnumbered those opposed to slavery, Coles managed to secure his election because the pro-slavery vote was split almost equally between Phillips and Brown, while Moore only won a few hundred votes.

Coles decided to force the issue of slavery on his very first day as governor in 1822, calling in his inaugural address before the Illinois General Assembly in Vandalia for the immediate emancipation of all slaves or indentured servants in Illinois. The pro-slavery members of the General Assembly responded by making plans to call for a new constitutional convention, with the unstated intention of crafting a constitution that would enshrine slave-owning as a right.

The resolution to put the question of calling a new convention to the people for a vote narrowly passed the Illinois House of Representatives by the slimmest of margins, and under extremely questionable circumstances. Initially the resolution failed by one vote when Nicholas Hansen of Pike County switched sides and voted against the resolution. But Hansen’s own election to the House had been marred by a vote-counting dispute – so his outraged pro-slavery colleagues expelled Hansen from the House and replaced him with his opponent in the election, John Shaw, who then obediently voted in favor of the resolution.

Even though the majority of Illinois voters and members of the General Assembly favored slavery, Dunne observed that, “The high-handed, arbitrary and unfair methods pursued by the House in evicting Hansen and securing thereby a two-thirds vote for the convention, disgusted many fair-minded citizens who had been tolerant of slavery.” Furthermore, although those who sought a new constitutional convention had the goal of turning Illinois from an officially free to an officially slave state, they were not forthright about their intentions, and that cynical approach probably cost them support.

Consequently, despite the numerical advantage and the initial momentum of those who wanted to call a constitutional convention, in the end their effort was resoundingly defeated on Aug. 2, 1824, by a vote of 6,640 to 4,972, “after a campaign of exceeding violence, lasting about eighteen months,” Dunne wrote. It had been an ugly fight, but Gov. Coles and his anti-slavery allies, including the influential journalists Morris Birkbeck and Daniel P. Cook (eponym of Cook County), managed to prevent the prospect of a pro-slavery constitution.

In retrospect, it can be seen that the very fate of the nation hung upon the outcome of Illinois’ convention battle – for if Illinois had switched from free to slave, the proponents of slavery would have gained permanent control of the U.S. Senate, “and no law thereafter could have been passed by Congress limiting or restricting slavery in the United States,” Dunne wrote.

The 1818 constitution limited governors to a single term, so Coles left office in 1826. Though he was able to defeat the convention movement, he was otherwise impotent against the pro-slavery General Assembly, which rejected all of his nominees to state office and ignored his legislative recommendations. Afterwards Coles was sued by the State for freeing his slaves without paying bonds of $200 to vouch for the good behavior of each freed slave. Even though he’d free his slaves before entering Illinois, the State initially won the politically-motivated suit – Coles would have had to pay $2,000, a great financial blow, but Coles appealed to the state Supreme Court and won on appeal.

Wearied by his bitter political experiences in Illinois, Coles returned to the East, finally settling in Philadelphia. He was gravely disappointed by his son Robert, who became a slave-owner and fought for the Confederacy – but he did live to see the abolition of slavery and emancipation of all slaves in the U.S. in the 1860s.

In 1929, a bronze portrait of Gov. Coles was erected in his memory in Valley View Cemetery in Edwardsville. Also, in recognition of Coles’ commitment to the abolition of slavery, the State of Illinois Human Rights Commission offers the Edward Coles Fellowship, a scholarship for law students.